Chapter 8.8: The many forms of Persian decline after Cyrus.

¶ 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1 4

1. Summary of Cyrus’ kingdom, governed by the will of Cyrus…

ὅτι μὲν δὴ καλλίστη καὶ μεγίστη τῶν ἐν τῇ Ἀσίᾳ ἡ Κύρου βασιλεία ἐγένετο αὐτὴ ἑαυτῇ μαρτυρεῖ. ὡρίσθη γὰρ πρὸς ἕω μὲν τῇ Ἐρυθρᾷ θαλάττῃ, πρὸς ἄρκτον δὲ τῷ Εὐξείνῳ πόντῳ, πρὸς ἑσπέραν δὲ Κύπρῳ καὶ Αἰγύπτῳ, πρὸς μεσημβρίαν δὲ Αἰθιοπίᾳ. τοσαύτη δὲ γενομένη μιᾷ γνώμῃ τῇ Κύρου ἐκυβερνᾶτο, καὶ ἐκεῖνός τε τοὺς ὑφ᾽ ἑαυτῷ ὥσπερ ἑαυτοῦ παῖδας ἐτίμα τε καὶ ἐθεράπευεν, οἵ τε ἀρχόμενοι Κῦρον ὡς πατέρα ἐσέβοντο.

¶ 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2 9

2. Yet when Cyrus dies his sons fall into dissension and nations revolt…

ἐπεὶ μέντοι Κῦρος ἐτελεύτησεν, εὐθὺς μὲν αὐτοῦ οἱ παῖδες ἐστασίαζον, εὐθὺς δὲ πόλεις καὶ ἔθνη ἀφίσταντο, πάντα δ᾽ ἐπὶ τὸ χεῖρον ἐτρέποντο. ὡς δ᾽ ἀληθῆ λέγω ἄρξομαι διδάσκων ἐκ τῶν θείων. οἶδα γὰρ ὅτι πρότερον μὲν βασιλεὺς καὶ οἱ ὑπ᾽ αὐτῷ καὶ τοῖς τὰ ἔσχατα πεποιηκόσιν εἴτε ὅρκους ὀμόσαιεν, ἠμπέδουν, εἴτε δεξιὰς δοῖεν, ἐβεβαίουν.

¶ 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3 2

3. This obedience to oaths was the basis on which people trusted the Persians…

εἰ δὲ μὴ τοιοῦτοι ἦσαν καὶ τοιαύτην δόξαν εἶχον οὐδ᾽ ἂν εἷς αὐτοῖς ἐπίστευεν, ὥσπερ οὐδὲ νῦν πιστεύει οὐδὲ εἷς ἔτι, ἐπεὶ ἔγνωσται ἡ ἀσέβεια αὐτῶν. οὕτως οὐδὲ τότε ἐπίστευσαν ἂν οἱ τῶν σὺν Κύρῳ ἀναβάντων στρατηγοί: νῦν δὲ δὴ τῇ πρόσθεν αὐτῶν δόξῃ πιστεύσαντες ἐνεχείρισαν ἑαυτούς, καὶ ἀναχθέντες πρὸς βασιλέα ἀπετμήθησαν τὰς κεφαλάς. πολλοὶ δὲ καὶ τῶν συστρατευσάντων βαρβάρων ἄλλοι ἄλλαις πίστεσιν ἐξαπατηθέντες ἀπώλοντο.

¶ 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4 4

4. In the past people used to win favor with the king by risking their life for him…

πολὺ δὲ καὶ τάδε χείρονες νῦν εἰσι. πρόσθεν μὲν γὰρ εἴ τις ἢ διακινδυνεύσειε πρὸ βασιλέως ἢ πόλιν ἢ ἔθνος ὑποχείριον ποιήσειεν ἢ ἄλλο τι καλὸν ἢ ἀγαθὸν αὐτῷ διαπράξειεν, οὗτοι ἦσαν οἱ τιμώμενοι: νῦν δὲ καὶ ἤν τις ὥσπερ Μιθριδάτης τὸν πατέρα Ἀριοβαρζάνην προδούς, καὶ ἤν τις ὥσπερ Ῥεομίθρης τὴν γυναῖκα καὶ τὰ τέκνα καὶ τοὺς τῶν φίλων παῖδας ὁμήρους παρὰ τῷ Αἰγυπτίῳ ἐγκαταλιπὼν καὶ τοὺς μεγίστους ὅρκους παραβὰς βασιλεῖ δόξῃ τι σύμφορον ποιῆσαι, οὗτοί εἰσιν οἱ ταῖς μεγίσταις τιμαῖς γεραιρόμενοι.

¶ 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5 4

5. In such a state of immorality all of those in Asia have turned to unholiness and injustice…

ταῦτ᾽ οὖν ὁρῶντες οἱ ἐν τῇ Ἀσίᾳ πάντες ἐπὶ τὸ ἀσεβὲς καὶ τὸ ἄδικον τετραμμένοι εἰσίν: ὁποῖοί τινες γὰρ ἂν οἱ προστάται ὦσι, τοιοῦτοι καὶ οἱ ὑπ᾽ αὐτοὺς ὡς ἐπὶ τὸ πολὺ γίγνονται. ἀθεμιστότεροι δὴ νῦν ἢ πρόσθεν ταύτῃ γεγένηνται.

¶ 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6 2

6. Persians are also dishonest about money by making people who have committed no crimes pay fines…

εἴς γε μὴν χρήματα τῇδε ἀδικώτεροι: οὐ γὰρ μόνον τοὺς πολλὰ ἡμαρτηκότας, ἀλλ᾽ ἤδη τοὺς οὐδὲν ἠδικηκότας συλλαμβάνοντες ἀναγκάζουσι πρὸς οὐδὲν δίκαιον χρήματα ἀποτίνειν: ὥστ᾽ οὐδὲν ἧττον οἱ πολλὰ ἔχειν δοκοῦντες τῶν πολλὰ ἠδικηκότων φοβοῦνται: καὶ εἰς χεῖρας οὐδ᾽ οὗτοι ἐθέλουσι τοῖς κρείττοσιν ἰέναι. οὐδέ γε ἁθροίζεσθαι εἰς βασιλικὴν στρατιὰν θαρροῦσι.

¶ 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7 3

7. Because of their impiety and injustice, they are prone to invasion from anyone who chooses.

τοιγαροῦν ὅστις ἂν πολεμῇ αὐτοῖς, πᾶσιν ἔξεστιν ἐν τῇ χώρᾳ αὐτῶν ἀναστρέφεσθαι ἄνευ μάχης ὅπως ἂν βούλωνται διὰ τὴν ἐκείνων περὶ μὲν θεοὺς ἀσέβειαν, περὶ δὲ ἀνθρώπους ἀδικίαν. αἱ μὲν δὴ γνῶμαι ταύτῃ τῷ παντὶ χείρους νῦν ἢ τὸ παλαιὸν αὐτῶν.

¶ 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8 4

8. They also do not worry about their bodies…

ὡς δὲ οὐδὲ τῶν σωμάτων ἐπιμέλονται ὥσπερ πρόσθεν, νῦν αὖ τοῦτο διηγήσομαι. νόμιμον γὰρ δὴ ἦν αὐτοῖς μήτε πτύειν μήτε ἀπομύττεσθαι. δῆλον δὲ ὅτι ταῦτα οὐ τοῦ ἐν τῷ σώματι ὑγροῦ φειδόμενοι ἐνόμισαν, ἀλλὰ βουλόμενοι διὰ πόνων καὶ ἱδρῶτος τὰ σώματα στερεοῦσθαι. νῦν δὲ τὸ μὲν μὴ πτύειν μηδὲ ἀπομύττεσθαι ἔτι διαμένει,

¶ 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9 4

9. They still eat only one meal, but this meal lasts all day long…

τὸ δ᾽ ἐκπονεῖν οὐδαμοῦ ἐπιτηδεύεται. καὶ μὴν πρόσθεν μὲν ἦν αὐτοῖς μονοσιτεῖν νόμιμον, ὅπως ὅλῃ τῇ ἡμέρᾳ χρῷντο εἰς τὰς πράξεις καὶ εἰς τὸ διαπονεῖσθαι. νῦν γε μὴν τὸ μὲν μονοσιτεῖν ἔτι διαμένει, ἀρχόμενοι δὲ τοῦ σίτου ἡνίκαπερ οἱ πρῳαίτατα ἀριστῶντες μέχρι τούτου ἐσθίοντες καὶ πίνοντες διάγουσιν ἔστεπερ οἱ ὀψιαίτατα κοιμώμενοι.

¶ 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10 4

10. They still do not bring pots to their banquets, but drink so much that they have to be carried out…

ἦν δ᾽ αὐτοῖς νόμιμον μηδὲ προχοΐδας εἰσφέρεσθαι εἰς τὰ συμπόσια, δῆλον ὅτι νομίζοντες τὸ μὴ ὑπερπίνειν ἧττον ἂν καὶ σώματα καὶ γνώμας σφάλλειν: νῦν δὲ τὸ μὲν μὴ εἰσφέρεσθαι ἔτι αὖ διαμένει, τοσοῦτον δὲ πίνουσιν ὥστε ἀντὶ τοῦ εἰσφέρειν αὐτοὶ ἐκφέρονται, ἐπειδὰν μηκέτι δύνωνται ὀρθούμενοι ἐξιέναι.

¶ 11

Leave a comment on paragraph 11 2

11. They still do not eat, drink, or go to the bathroom on a march, but now their marches are short…

ἀλλὰ μὴν κἀκεῖνο ἦν αὐτοῖς ἐπιχώριον τὸ μεταξὺ πορευομένους μήτε ἐσθίειν μήτε πίνειν μήτε τῶν διὰ ταῦτα ἀναγκαίων μηδὲν ποιοῦντας φανεροὺς εἶναι: νῦν δ᾽ αὖ τὸ μὲν τούτων ἀπέχεσθαι ἔτι διαμένει, τὰς μέντοι πορείας οὕτω βραχείας ποιοῦνται ὡς μηδέν᾽ ἂν ἔτι θαυμάσαι τὸ ἀπέχεσθαι τῶν ἀναγκαίων.

¶ 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12 2

12. They do not go out hunting anymore since Artaxerxes and his court became drunkards…

ἀλλὰ μὴν καὶ ἐπὶ θήραν πρόσθεν μὲν τοσαυτάκις ἐξῇσαν ὥστε ἀρκεῖν αὐτοῖς τε καὶ ἵπποις γυμνάσια τὰς θήρας: ἐπεὶ δὲ Ἀρταξέρξης ὁ βασιλεὺς καὶ οἱ σὺν αὐτῷ ἥττους τοῦ οἴνου ἐγένοντο, οὐκέτι ὁμοίως οὔτ᾽ αὐτοὶ ἐξῇσαν οὔτε τοὺς ἄλλους ἐξῆγον ἐπὶ τὰς θήρας: ἀλλὰ καὶ εἴ τινες φιλόπονοι γενόμενοι καὶ σὺν τοῖς περὶ αὑτοὺς ἱππεῦσι θαμὰ θηρῷεν, φθονοῦντες αὐτοῖς δῆλοι ἦσαν καὶ ὡς βελτίονας αὑτῶν ἐμίσουν.

¶ 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13 4

13. Boys are still educated at court, but not in horsemanship or justice…

ἀλλά τοι καὶ τοὺς παῖδας τὸ μὲν παιδεύεσθαι ἐπὶ ταῖς θύραις ἔτι διαμένει: τὸ μέντοι τὰ ἱππικὰ μανθάνειν καὶ μελετᾶν ἀπέσβηκε διὰ τὸ μὴ εἶναι ὅπου ἂν ἀποφαινόμενοι εὐδοκιμοῖεν. καὶ ὅτι γε οἱ παῖδες ἀκούοντες ἐκεῖ πρόσθεν τὰς δίκας δικαίως δικαζομένας ἐδόκουν μανθάνειν δικαιότητα, καὶ τοῦτο παντάπασιν ἀνέστραπται: σαφῶς γὰρ ὁρῶσι νικῶντας ὁπότεροι ἂν πλέον διδῶσιν.

¶ 14

Leave a comment on paragraph 14 4

14. Whereas they used to learn about produce from the earth, now they just learn about poisons…

ἀλλὰ καὶ τῶν φυομένων ἐκ τῆς γῆς τὰς δυνάμεις οἱ παῖδες πρόσθεν μὲν ἐμάνθανον, ὅπως τοῖς μὲν ὠφελίμοις χρῷντο, τῶν δὲ βλαβερῶν ἀπέχοιντο: νῦν δὲ ἐοίκασι ταῦτα διδασκομένοις, ὅπως ὅτι πλεῖστα κακοποιῶσιν: οὐδαμοῦ γοῦν πλείους ἢ ἐκεῖ οὔτ᾽ ἀποθνῄσκουσιν οὔτε διαφθείρονται ὑπὸ φαρμάκων.

¶ 15

Leave a comment on paragraph 15 8

15. They are also more effeminate than in Cyrus’ day…

ἀλλὰ μὴν καὶ θρυπτικώτεροι πολὺ νῦν ἢ ἐπὶ Κύρου εἰσί. τότε μὲν γὰρ ἔτι τῇ ἐκ Περσῶν παιδείᾳ καὶ ἐγκρατείᾳ ἐχρῶντο, τῇ δὲ Μήδων στολῇ καὶ ἁβρότητι: νῦν δὲ τὴν μὲν ἐκ Περσῶν καρτερίαν περιορῶσιν ἀποσβεννυμένην, τὴν δὲ τῶν Μήδων μαλακίαν διασῴζονται.

¶ 16

Leave a comment on paragraph 16 2

16. Now their couches are set upon carpets to provide further cushion…

σαφηνίσαι δὲ βούλομαι καὶ τὴν θρύψιν αὐτῶν. ἐκείνοις γὰρ πρῶτον μὲν τὰς εὐνὰς οὐ μόνον ἀρκεῖ μαλακῶς ὑποστόρνυσθαι, ἀλλ᾽ ἤδη καὶ τῶν κλινῶν τοὺς πόδας ἐπὶ ταπίδων τιθέασιν, ὅπως μὴ ἀντερείδῃ τὸ δάπεδον, ἀλλ᾽ ὑπείκωσιν αἱ τάπιδες. καὶ μὴν τὰ πεττόμενα ἐπὶ τράπεζαν ὅσα τε πρόσθεν ηὕρητο, οὐδὲν αὐτῶν ἀφῄρηται, ἄλλα τε ἀεὶ καινὰ ἐπιμηχανῶνται: καὶ ὄψα γε ὡσαύτως: καὶ γὰρ καινοποιητὰς ἀμφοτέρων τούτων κέκτηνται.

¶ 17

Leave a comment on paragraph 17 4

17. They need very thick clothes in winter…

ἀλλὰ μὴν καὶ ἐν τῷ χειμῶνι οὐ μόνον κεφαλὴν καὶ σῶμα καὶ πόδας ἀρκεῖ αὐτοῖς ἐσκεπάσθαι, ἀλλὰ καὶ περὶ ἄκραις ταῖς χερσὶ χειρῖδας δασείας καὶ δακτυλήθρας ἔχουσιν. ἔν γε μὴν τῷ θέρει οὐκ ἀρκοῦσιν αὐτοῖς οὔθ᾽ αἱ τῶν δένδρων οὔθ᾽ αἱ τῶν πετρῶν σκιαί, ἀλλ᾽ ἐν ταύταις ἑτέρας σκιὰς ἄνθρωποι μηχανώμενοι αὐτοῖς παρεστᾶσι.

¶ 18

Leave a comment on paragraph 18 2

18. They are greedy to have as many cups as possible; they have a sordid love of gain…

καὶ μὴν ἐκπώματα ἢν μὲν ὡς πλεῖστα ἔχωσι, τούτῳ καλλωπίζονται: ἢν δ᾽ ἐξ ἀδίκου φανερῶς ᾖ μεμηχανημένα, οὐδὲν τοῦτο αἰσχύνονται: πολὺ γὰρ ηὔξηται ἐν αὐτοῖς ἡ ἀδικία τε καὶ αἰσχροκέρδεια.

¶ 19

Leave a comment on paragraph 19 2

19. They still travel on horseback but with many more coverings than before…

ἀλλὰ καὶ πρόσθεν μὲν ἦν ἐπιχώριον αὐτοῖς μὴ ὁρᾶσθαι πεζῇ πορευομένοις, οὐκ ἄλλου τινὸς ἕνεκα ἢ τοῦ ὡς ἱππικωτάτους γίγνεσθαι: νῦν δὲ στρώματα πλείω ἔχουσιν ἐπὶ τῶν ἵππων ἢ ἐπὶ τῶν εὐνῶν: οὐ γὰρ τῆς ἱππείας οὕτως ὥσπερ τοῦ μαλακῶς καθῆσθαι ἐπιμέλονται. Rodrigo Santoro as the Persian king Xerxes in Zack Snyder’s “300.”

Rodrigo Santoro as the Persian king Xerxes in Zack Snyder’s “300.”

¶ 20

Leave a comment on paragraph 20 6

20. They make knights out of all sorts of people from bakers to the people that apply their make-up…

τά γε μὴν πολεμικὰ πῶς οὐκ εἰκότως νῦν τῷ παντὶ χείρους ἢ πρόσθεν εἰσίν; οἷς ἐν μὲν τῷ παρελθόντι χρόνῳ ἐπιχώριον εἶναι ὑπῆρχε τοὺς μὲν τὴν γῆν ἔχοντας ἀπὸ ταύτης ἱππότας παρέχεσθαι, οἳ δὴ καὶ ἐστρατεύοντο εἰ δέοι στρατεύεσθαι, τοὺς δὲ φρουροῦντας πρὸ τῆς χώρας μισθοφόρους εἶναι: νῦν δὲ τούς τε θυρωροὺς καὶ τοὺς σιτοποιοὺς καὶ τοὺς ὀψοποιοὺς καὶ οἰνοχόους καὶ λουτροχόους καὶ παρατιθέντας καὶ ἀναιροῦντας καὶ κατακοιμίζοντας καὶ ἀνιστάντας, καὶ τοὺς κοσμητάς, οἳ ὑποχρίουσί τε καὶ ἐντρίβουσιν αὐτοὺς καὶ τἆλλα ῥυθμίζουσι, τούτους πάντας ἱππέας οἱ δυνάσται πεποιήκασιν, ὅπως μισθοφορῶσιν αὐτοῖς.

¶ 21

Leave a comment on paragraph 21 2

21. They are of no use in war…

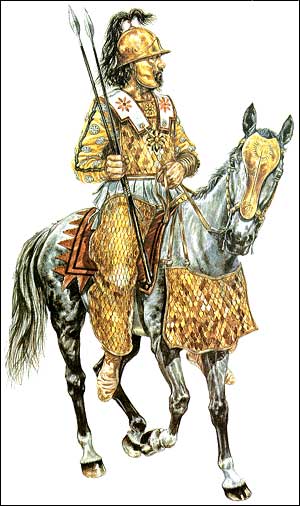

πλῆθος μὲν οὖν καὶ ἐκ τούτων φαίνεται, οὐ μέντοι ὄφελός γε οὐδὲν αὐτῶν εἰς πόλεμον: δηλοῖ δὲ καὶ αὐτὰ τὰ γιγνόμενα: κατὰ γὰρ τὴν χώραν αὐτῶν ῥᾷον οἱ πολέμιοι ἢ οἱ φίλοι ἀναστρέφονται. The fully-armed Achaemenid cavalry horseman.

The fully-armed Achaemenid cavalry horseman.

¶ 22

Leave a comment on paragraph 22 2

22. They do not fight hand-to-hand anymore or even skirmish at a distance…

καὶ γὰρ δὴ ὁ Κῦρος τοῦ μὲν ἀκροβολίζεσθαι ἀποπαύσας, θωρακίσας δὲ καὶ αὐτοὺς καὶ ἵππους καὶ ἓν παλτὸν ἑκάστῳ δοὺς εἰς χεῖρα ὁμόθεν τὴν μάχην ἐποιεῖτο: νῦν δὲ οὔτε ἀκροβολίζονται ἔτι οὔτ᾽ εἰς χεῖρας συνιόντες μάχονται.

¶ 23

Leave a comment on paragraph 23 5

23. The infantry have the same armor as in the days of Cyrus but are unwilling to fight hand-to-hand…

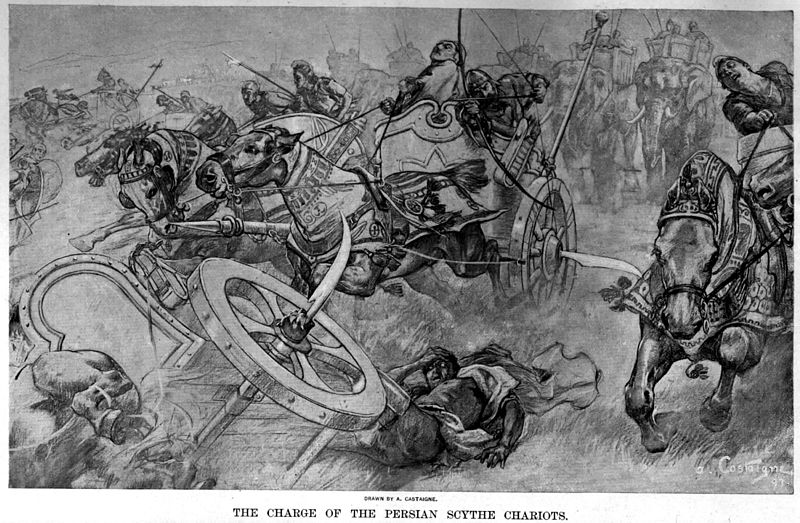

καὶ οἱ πεζοὶ ἔχουσι μὲν γέρρα καὶ κοπίδας καὶ σαγάρεις ὥσπερ οἱ ἐπὶ Κύρου τὴν μάχην ποιησάμενοι: εἰς χεῖρας δὲ ἰέναι οὐδ᾽ οὗτοι ἐθέλουσιν. “The charge of the Persian scythed chariots at the Battle of Gaugamela,” by Andre Castaigne (1898-1899).

“The charge of the Persian scythed chariots at the Battle of Gaugamela,” by Andre Castaigne (1898-1899).

¶ 24

Leave a comment on paragraph 24 8

24. They do not use chariots as Cyrus had, nor do they train them, nor do the officers know their names…

οὐδέ γε τοῖς δρεπανηφόροις ἅρμασιν ἔτι χρῶνται ἐφ᾽ ᾧ Κῦρος αὐτὰ ἐποιήσατο. ὁ μὲν γὰρ τιμαῖς αὐξήσας τοὺς ἡνιόχους καὶ ἀγαστοὺς ποιήσας εἶχε τοὺς εἰς τὰ ὅπλα ἐμβαλοῦντας: οἱ δὲ νῦν οὐδὲ γιγνώσκοντες τοὺς ἐπὶ τοῖς ἅρμασιν οἴονται σφίσιν ὁμοίους τοὺς ἀνασκήτους τοῖς ἠσκηκόσιν ἔσεσθαι.

¶ 25

Leave a comment on paragraph 25 2

25. They will charge but in a haphazard and ineffective manner…

οἱ δὲ ὁρμῶσι μέν, πρὶν δ᾽ ἐν τοῖς πολεμίοις εἶναι οἱ μὲν ἄκοντες ἐκπίπτουσιν, οἱ δ᾽ ἐξάλλονται, ὥστε ἄνευ ἡνιόχων γιγνόμενα τὰ ζεύγη πολλάκις πλείω κακὰ τοὺς φίλους ἢ τοὺς πολεμίους ποιεῖ.

¶ 26

Leave a comment on paragraph 26 5

26. They don’t go to war without Greek mercenaries…

ἐπεὶ μέντοι καὶ αὐτοὶ γιγνώσκουσιν οἷα σφίσι τὰ πολεμιστήρια ὑπάρχει, ὑφίενται, καὶ οὐδεὶς ἔτι ἄνευ Ἑλλήνων εἰς πόλεμον καθίσταται, οὔτε ὅταν ἀλλήλοις πολεμῶσιν οὔτε ὅταν οἱ Ἕλληνες αὐτοῖς ἀντιστρατεύωνται: ἀλλὰ καὶ πρὸς τούτους ἐγνώκασι μεθ᾽ Ἑλλήνων τοὺς πολέμους ποιεῖσθαι.

¶ 27

Leave a comment on paragraph 27 8

27. In conclusion, present day Persians are less reverent, less dutiful, less just, and less brave…

ἐγὼ μὲν δὴ οἶμαι ἅπερ ὑπεθέμην ἀπειργάσθαι μοι. φημὶ γὰρ Πέρσας καὶ τοὺς σὺν αὐτοῖς καὶ ἀσεβεστέρους περὶ θεοὺς καὶ ἀνοσιωτέρους περὶ συγγενεῖς καὶ ἀδικωτέρους περὶ τοὺς ἄλλους καὶ ἀνανδροτέρους τὰ εἰς τὸν πόλεμον νῦν ἢ πρόσθεν ἀποδεδεῖχθαι. εἰ δέ τις τἀναντία ἐμοὶ γιγνώσκοι, τὰ ἔργα αὐτῶν ἐπισκοπῶν εὑρήσει αὐτὰ μαρτυροῦντα τοῖς ἐμοῖς λόγοις.

Does the epilogue (Cyropaedia 8.8 ) undercut or subvert the content of the rest of the Cyropaedia? Do we have reasons to doubt whether Xenophon wrote this? If it is by Xenophon, how does it alter our perceptions of the rest of the work? If it is by someone else and has somehow become attached to the text, what was it about the text that bothered the author of the epilogue?

The authenticity of this chapter, the so-called epilogue, has long been the subject of scholarly dispute. I wrote about this in The Friendship of the Barbarians,Hirsch 1985:91-96 , and I must say that, upon rereading it after a long time away from this material, my argument still seems persuasive to me, but then what do you expect! While most 19th-century scholars denied that it could have been written by Xenophon, the majority of 20th century scholars accepted its authenticity. I felt strongly that it could not have been part of the original text. It blatantly contradicts many of Xenophon’s assertions earlier in the text, most particularly those places where Xenophon claimed that some Persian practice was still being maintained in his time (eti kai nun…), and virtually all the loci that contradict material elsewhere in the work are clustered in the epilogue. Some scholars claim that the style of the epilogue is consistent with that of Xenophon. “Style” is, of course, a slippery beast, prone to much subjectivity. Perhaps someone skilled in computer analysis will be able to pose a set of concrete questions about countable linguistic phenomena and compare it to other patches of Xenophon. In any case, the tone of the epilogue – “sarcastic, abusive, sometimes even vulgar” – does not feel like Xenophon to me. Finally, I argued that if, as many believe, Plato Laws book 3 is reacting to Xenophon’s Cyropaedia, then his text of the Cyropaedia did not contain the epilogue, for it would have already done his work for him in showing how far Persia had declined from the virtues of the past.I have not been working on this material or keeping up with the scholarship for quite a while, so I would be glad to hear from others about more recent discussions of this problem.

It seems to me likely to be authentically Xenophon’s, as it seems to conform with his personal experience of the Persians in the retreat of the Ten Thousand, as well as his experience as an Athenian with Persian attempts at bribery and bullying from 420 or so to the Peace of Antalcidas, and the general Greek experience of almost uniform success in combat against the Persians for over 100 years. In fact, one might argue from a Greek perspective that Xenophon would have been forced to write this palinode in order to explain the difference between the Cyrus the Great he imagines and the Persians the Greeks actually knew.

Although we should keep in mind that Artaxerxes I fought the Athenians to a draw, and that Darius II and Artaxerxes II both won their respective Ionian Wars decisively. Like the Hundred Years’ War, we tend to remember a few battles more than the general course of events. It is very likely that our sources are biased towards anti-Persian and Panhellenic sentiments, because after Alexander those seemed like the ‘right’ ones. The frequent references to Xenophon’s experiences inCyropaedia 8.8 could mean Xenophon was the writer, or that the interpolator was familiar with his works. I wonder if the papyri are any help?

I cannot decide which is more generous – “draw” or “fought” in reference to Artaxerxes 1 – he spent most of his time funding proxies, as I recall. Darius II waited for the Syracusans to do the hard work of beating the Athenians, then went to work on the Ionians, and I seriously doubt that X. had any good opinion of Artaxerxes II, for obvious reasons.

I agree with Sean. The Persians were successful most of the time, from the late fifth century on, in keeping the Greeks weak, divided, and demoralized, largely through a simple combination of money, threats, and strategic alliances. They decided the outcome of the Peloponnesian War, thereby destroying their nemesis, the Athenian Empire, and recouping (through their treaties with Sparta) their former territories in Asia. They used money in the war of the 390s to force Sparta to withdraw its troops from Ionia and bog it down in a trench war around Corinth, and the naval victory over the Spartans at Cnidus made them masters of Aegean waters. The King’s Peace was a dictate, with the autonomy clause keeping the Greeks fragmented, and Sparta serving as their enforcer through the 380s and 370s, and Thebes taking over that role in the 360s. If Persia didn’t have internal troubles of its own (secession of Egypt, various revolts), they might well have contemplated another invasion of Greece. At mid-century, after the Egyptian revolt had been crushed and Ochus was on the throne – arguably the most formidable military commander since Darius I – Persia looked as strong as ever. No wonder Philip got so much mileage out of the Persian threat, getting himself appointed hegemon of the Greeks – the Greeks were scared. Nobody could have foreseen Alexander, but our views, and those of Greeks in later times, tend to be colored by our knowledge of his success. The Greeks may have regarded Persian tactics as dirty pool, but by any objective standards it was successful – Greece was weak, and Persia appeared to be as formidable and threatening as ever. Indeed, worldly Greeks like Xenophon, who chronicled all this in the Hellenica, must have been ashamed of how easily the Greeks had been played. I suppose you could use this history to argue that the Greeks were bitter about the way the Persians dealt with them, and that we’re seeing that bitterness in the accusations in the epilogue. But Xenophon could never say, as Isocrates did, that Persia was weak and the proof was that the Ten Thousand had a cakewalk on their way home.

You both seem only to articulate my point, that it was Persian money and strategy, rather than valor, that allowed them to do as well as they did – and the Spartan withdrawal from Asia Minor had as much to do with Sparta betraying the Greek cause as Persian victory – and an oft-overlooked aspect of the battle at Salamis in Cyprus is that the Athenians, in fact, did win. Only the misadventure of Egypt is a secure “loss” and tells more of the overreach of the Athenians than of Persian capabilities. As for the “cakewalk” of the retreat, Persian treachery and the geography of empire had more to do with that than any martial capacity of the Persians.

In the day of Artaxerxes I, the Athenians and their allies were thrown out of Egypt and had to agree to withdraw from Cyprus in exchange for peace along the Aegean coast. They got to keep the coast, but they had controlled that when Artaxerxes took the throne. Given that Athens had dreamed of taking Cyprus and putting a friendly king in Egypt, I would call that a draw. I certainly think that from the 470s to 394, whichever Greek power was strongest could hold the ports and march around the coast of Anatolia enslaving farmers and burning villages, but they found it very hard to do more than that. Xenophon actually admits the limitations of being able to march where you like but not take walled places when when he compares an army moving through enemy territory without taking cities to a ship sailing the sea (Cyropaedia 6.1.16 ).

Much of your argument seems to depend on accepting the authenticity of the Peace of Kallias – do you?

While it is always fun to discuss essentially irresolvable (with our current evidence) problems like the Peace of Callias, my own take on it is that it’s not that significant – whether or not there was a formal treaty, there was clearly some sort of understanding between Athens and Persia that prevailed from midcentury till the last phase of the Peloponnesian war. The Athenian Empire was strong enough to keep the Persians out of the Aegean, and fourth century Greeks looked back on Greece’s relative strength at that time longingly. But what is more relevant to this enterprise – the circumstances in which the Cyropaedia, and more specifically the epilogue, was written – is the situation in the fourth century and the Greeks’ perception of it, which I tried to address in my previous comment. You and the Greeks may not like the way the Persians operated, but the reality was that they were largely successful and that they did not appear to be weak. To the extent that the epilogue stresses Persian weakness, I have difficulty believing Xenophon saw it that way. Isocrates and a few others may have claimed that in order to advance their agenda, and the composer of the epilogue may have been one of these, or someone, like Plato, who objected to Xenophon’s moral idealization of the Persians, or someone writing after Alexander’s conquest, when the weakness of the Persians was apparent in retrospect.

I cannot agree that the Persians didn’t look weak, except in retrospect – there were certainly those who overrated their strength, of course. I doubt that Xenophon would have been one of them, but in the end, that is also an unanswerable question.

I’m not sure it does depend. It seems to me that the evidence is reasonably clear that fighting between the Delian League and Artaxerxes ended around 450 with the Greek withdrawal from Cyprus, and that whether you believe there was a treaty, an informal agreement, or just mutual exhaustion there still was peace. For my thesis I am provisionally accepting a treaty around 448 (the “Peace of Callias”). My views are similar to DavidLewis CAH 2nd Ed. Vol. 5 pp. 121-127 .

I think that it does – it makes what may be merely strategic exhaustion into a diplomatic victory that evanesces upon inspection. As for the rest, from Thermopylae to Knidos, the Persians won no significant battles outside of finishing off a stranded Greek army in Egypt – and at Thermopylae, they enjoyed an almost ridiculous numerical advantage, while at Knidos, they won the battle with an Athenian admiral. (I omit Cunaxa as a special case, since the Greeks were clearly not defeated, but Artaxerxes did win the battle. Like it or not, I doubt that any Greek hoplite thought of his Persian counterpart as much of a threat, and that deterioration of martial vigor required explanation from X. As to strategic or diplomatic advantages, the Persians did have the advantage that they could play “divide and annoy” with the Greeks, which points to the inferiority of the polis system and X.’s possible dissatisfaction with it that I pointed out in an earlier post. But even the King’s Peace didn’t achieve a great deal for the Persians.

This is a fascinating question. On the issue of style, and as you point out in the book (Hirsch 1985:94 ), stylistic assertions about this passage are often subjective and short on specific features that we might use to gauge authenticity. One potential line of investigation here is to use computer analysis. I wonder whether others know of any analysis along these lines already? In the interest of getting more specific data on this question, I had before run some data mining tests on Xenophon’s corpus against various non-Xenophon sets. (There are a number of limitations here– an incomplete corpus of prose, certain omissions; I mention this here only as an initial foray into this question.) A lot of what you get back is an artifact of the small corpus size and overfits the content of the material. That is, even though the statistical test will pick up all types of information and, in cases where sociolinguistic patterns are quantifiable (e.g. male vs. female speech, high status vs. low status speech) will be quite revealing about important markers of differences in language, for the Xenophon vs. not Xenophon test I am so far finding that it is not much better than noise. For what it is worth though, this section (Cyropaedia 8.8 ) has some of the markers of “Xenophon” and very few of the markers that I’m getting for “Not Xenophon”. I don’t think that proves anything, as one needs more data and I offer this only as a quick and dirty result of some initial tests, but I suspect it reflects the problem and maybe a restatement of the question. How would we know whether it is Xenophon or not? Or, rather, would you imagine that anyone reading this in antiquity would have difficulty imagining in is authentic Xenophon? More if I can find anything that is not noise in these sorts of statistical tests…

I have just a few thoughts here on what is, as Allen says, a fascinating (and complex) question. By my count using the Bude editions, Book Eight is considerably longer than any other book in the Cyropaedia at 67 pages, nearly seven of which are devoted to Cyropaedia 8.8. It is nearly twice as long as the shortest book, Book Two at 36 pages, and 20% longer than the second longest book, Book One at 56 pages. If we remove the seven pages of 8.8, then Book Eight is only 7% longer than Book One. This is by no means a proof of inauthenticity, but I think it’s worth considering.

On Allen’s question on how readers in antiquity would have readCyropaedia 8.8 , I am puzzled: would the “forger” not have known Greek better than perhaps any modern reader and not have expected to pass off his writing as Xenophontic to readers who also knew Greek better than modern readers? Similarly, where 8.8 conflicts with claims about the Persians in Book One, who is more likely to have engaged in a contradiction, Xenophon (who wrote Book One) or the “forger”, who had read Book One presumably a bunch of times and would have hoped to remain consistent with what Xenophon says throughout the work. If we as 20th and 21st century readers can detect such contradictions fairly easily, why would a “forger” have been so careless? I agree with Hirsch 1985:94 that it is very disturbing to see Xenophon making disparaging remarks about all Persians, rather than a degenerate few. Nevertheless, Xenophon may be buying into the Herodotean idea that all groups of people decline over time. I don’t have strong views about the authenticity of Cyropaedia 8.8, but I have always found them to be consistent with the pessimistic tone of the first sentence of the work and with Cambyses’ remarks at Cyropaedia 1.6.45 . In any case, pace Plato and others, I don’t see Persian degeneracy in Cyropaedia 8.8 as necessarily a strike against Cyrus.

What are the major sections ofCyropaedia 8.8 ?

Section outline and overview:

Cyropaedia 8.8.1 Restatement of Cyrus’ great achievements and accomplishments as a leader.

How does the epilogue (Cyropaedia 8.8 ) differ in tone from the rest of Cyropaedia?

The epilogue seemingly does an about-face from the rest of the Cyropaedia. It moves from celebrating Cyrus as an ideal leader and Persia as a great empire to anti-Persian propaganda.Hirsch 1985:94 calls the epilogue’s tone “sarcastic, abusive and sometimes even vulgar” (see also Gray 2011:255 ). And if Persian power and education dissolve so quickly after Cyrus’ death, the epilogue at least begs the question of whether Cyrus was truly a great leader, or in some way the harbinger of Persian political and moral decay. Furthermore, Cyropaedia 8.8 mocks Xenophon’s contemporary Persians as weak and effeminate, and so adopts an Orientalizing posture not present (or at least far less explicit) in the main body of Cyropaedia. On Orientalism in Cyropaedia 8.8 , see my comments on Cyropaedia 8.8.15 .

Because of its perceived shift in tone from the rest of Cyropaedia,Cyropaedia 8.8 has prompted at least two major interrelated questions in its modern scholarly reception: 1) Is the chapter authentic, or a spurious later addition? 2) Is the chapter coherent with, or inimical to, Xenophon’s treatment of Cyrus and depictions of Persia throughout the main body of Cyropaedia?

Does the turn Xenophon takes inCyropaedia 8.8 cast doubts upon the authenticity of the epilogue?

Over the past several centuries, numerous scholars have doubted the authenticity ofCyropaedia 8.8 . Sage 1995 traces these doubts about Cyropaedia 8.8 ’s authenticity to Valckenaer 1766 . The view that Cyropaedia 8.8 must be spurious was especially prominent in nineteenth century scholarship. See, for example, Holden 1890:196-97 and Goodwin 1879:165-66 . In more contemporary scholarship, Steven W. Hirsch 1985 similarly casts aspersions on the authenticity of Cyropaedia 8.8 , especially because its anti-Persian sentiment appears inconsistent with the rest of Cyropaedia.

Against Hirsch’s view,Eichler 1880 argues “for Xenophon’s authorship of 8.8 on linguistic and stylistic grounds” (see Sage 1995:161n3 ). More recent defenders of the authenticity of Cyropaedia 8.8 include Field 2012 , Johnson 2005 , Müller-Goldingen 1995 , Sage 1995 , Due 1989 , Tatum 1989 , and Delebecque 1957 . Christesen 2006:56 accepts that, despite the controversy surrounding its authenticity, Cyropaedia 8.8 “is now generally taken to be an integral part of the work.”

Can the epilogue be reconciled with the main body of Cyropaedia?

Those who doubt the authenticity ofCyropaedia 8.8 very consistently point to the epilogue’s inconsistency with the rest of Cyropaedia. For instance, Hirsch 1985:93 points to the fact that:

“Flagrant contradictions between the epilogue and the main body of the text are to be found. It is hard to believe that these are mere oversights, the more so since no such striking internal contradictions surface within the body of the work… The contradictions are there, they are glaring, and they are unparalleled elsewhere in the work. They cannot be glossed over.”

Belief that the epilogue is not Xenophon’s own original conclusion to Cyropaedia uniformly goes hand in hand with the opinion that the apparent change in tone and the inconsistencies of 8.8 (often involving ἔτι καὶ νῦν constructions) are irreconcilable with Cyropaedia’s main body of text. Similarly, critics of the epilogue’s authenticity argue thatCyropaedia 8.7 provides a natural conclusion to Cyropaedia and that the tone of the epilogue is atypical of Xenophon’s writing in other works (Hirsch 1985:94 ).

Those who defend the authenticity ofCyropaedia 8.8 are divided over whether the epilogue is consistent with the rest of Cyropaedia’s portrayal of Cyrus and construction of Persia. Delebecque 1957:405 , for example, reads Cyropaedia 8.8 as disharmonious with the rest of Cyropaedia. Others who defend the Cyropaedia’s positive view of Cyrus, yet accept Cyropaedia 8.8 as authentic include Due 1989:16-22 ; Müeller-Goldingen 1995:262-71 ; Tatum 1989:215-39 . Sage 1995:161 invokes the authority of the manuscript tradition in her defense of the epilogue’s authenticity. Sage 1995:162 argues that Cyropaedia 8.8 “is appropriate both rhetorically and thematically, and enriches, rather than undercuts” the main body of the Cyropaedia. In this interpretation, Xenophon’s conclusion confirms Cyropaedia’s introductory statements about the difficulty of ruling men, while reaffirming the exceptional greatness of Cyrus by contrast with his successors. See also Tuplin 2004:326 : “Cyrus is a necessarily flawed hero, but still a hero, and the quasi-mystic quality to his end (whatever it owes to Iranian story-telling) reflects this, just as the palinode both assures us that praise of a Persian is not to be taken wholly outside the context of fourth-century Greek reactions to the empire and underlines that the fourth-century empire is a squalid remnant of a grand, if intrinsically flawed, experiment.”

Others, however, argue that the epilogue is in keeping with what comes before it in Cyropaedia.Johnson 2005:180-81 reads the whole of Cyropaedia as unfavorable towards Cyrus and takes Cyropaedia 8.8 as consistent with Xenophon’s larger program: “The decline in the Persian character begins not after Cyrus’ death, or even with his organization of his empire, but with Cyrus’ initial transformation of the Persians into an army of conquest, a transformation that corrupts the pristine Persia of Cyrus’ youth.” Johnson argues that “Cyrus’ transformed Persians are inherently unstable.” In this view, the epilogue invites us to reread Cyropaedia more critically. Johnson 2005:204-05 argues that Xenophon’s ancient audience “would have been less surprised than we by the epilogue.” Johnson situates Cyropaedia in a Socratic tradition, which challenged readers to think through issues by themselves: “Xenophon would… have his readers recognize the perilous attractions of empire, for both rulers and subjects, by falling prey to those attractions themselves.” Laura Field 2012:724-25 ‘s reading is similar: “the bleak finale casts a shadow back over the rest of the text… and acts as a deliberate invitation to consider the book and its protagonist anew…. Xenophon’s work is at bottom so seriously critical of Cyrus’ rule that the ending of the book must be considered a wholly fitting one.”

ErichGruen 2011:64-65 makes a particularly creative attempt to integrate Cyropaedia 8.8 with the main body of Cyropaedia. Gruen argues that Xenophon lauded Cyrus and the Persians at a cultural moment with leanings towards jingoism and Orientalism. As I note in my comments on Cyropaedia 8.8.15 , Gruen suggests that Xenophon parodies Greek stereotypes of Persia. In so doing, “the historian stole a march on potential critics. He discredited the clichés by exaggerating them with parody and reducing them to absurdity.”

AsGray 2011: 256n14 notes, the approach of James O’Hara 2006 to inconsistency in ancient poetry may well apply here. It is more productive to interpret rather than remove (for instance by striking them from the text is inauthentic) or explain away inconsistency (for instance Gera’s assumption of sloppiness on the part of the author; Gera 1993:299-300 ). O’Hara 2006:3 posits a willingness on the part of ancient authors to make use of inconsistency. O’Hara 2006:2 argues of Virgil’s Aeneid that contradictions might serve to deceive readers, or at least offer conflicting paths of interpretation (a suggestion evocative of Johnson’s dark, Socratic reading of Cyropaedia). In the case of Xenophon, the demands of rhetoric and the element of surprise may account for dissonance between much of Cyropaedia 8.8 and the Cyropaedia’s main body of text. Tatum 1989:224 suggests that, “for Xenophon, the gap between the political and historical world he lived in and the romantically successful but fictional world of the Cyropaedia finally outweighed his authorial desire to preserve the integrity of the text he had created.”

This is not to say, however, that the inconsistences and contradictions of 8.8 can be easily dismissed, andGera 1993:299 is too quick to brush these contradictions aside on the grounds that they concern “unimportant” matters. That said, I do not believe the mere existence of inconsistencies between Cyropaedia’s epilogue and main body warrants dismissing Cyropaedia 8.8 as inauthentic. The Epilogue may be a later addition and of spurious authorship, but this is by no means the only possible explanation for the contradictions of Cyropaedia 8.8 .

In a sense, how to approach the inconsistencies ofCyropaedia 8.8 may hinge on whether one brings an author-centered or reader-centered hermeneutic to bear on the text. For Hirsch 1985 and 19th century philologists who earlier questioned the authenticity of Cyropaedia 8.8 , “Who wrote the epilogue and why?” are essential questions. However, a reader-centered approach will note that the manuscript tradition suggests that audiences were reading Cyropaedia 8.8 as the conclusion to Cyropaedia from an early date and that the ancients seem to have accepted it as part of the text. In this view, the authorship (or not) of Xenophon becomes secondary to the role that the epilogue plays in the text as Cyropaedia’s readers have received it for more than two millennia.