Chapter 1.2: The Persian Moral and Martial Education

¶ 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1 52

1. Cyrus’ Birth and Nature…

πατρὸς μὲν δὴ ὁ Κῦρος λέγεται γενέσθαι Καμβύσου Περσῶν βασιλέως:  What is the relationship between Xenophon’s account of Cyrus’ birth and Herdototus’ in the Histories 1.108? ὁ δὲ Καμβύσης οὗτος τοῦ Περσειδῶν γένους ἦν:

What is the relationship between Xenophon’s account of Cyrus’ birth and Herdototus’ in the Histories 1.108? ὁ δὲ Καμβύσης οὗτος τοῦ Περσειδῶν γένους ἦν:  What does a beautiful leader look like? What effect does beauty have on leadership and leadership on beauty?οἱ δὲ Περσεῖδαι ἀπὸ Περσέως κλῄζονται: μητρὸς δὲ ὁμολογεῖται Μανδάνης γενέσθαι: ἡ δὲ Μανδάνη αὕτη Ἀστυάγους ἦν θυγάτηρ τοῦ Μήδων γενομένου βασιλέως. φῦναι δὲ ὁ Κῦρος λέγεται καὶ ᾁδεται ἔτι καὶ νῦν ὑπὸ τῶν βαρβάρων εἶδος μὲν κάλλιστος, ψυχὴν δὲ φιλανθρωπότατος καὶ φιλομαθέστατος καὶ φιλοτιμότατος, ὥστε πάντα μὲν πόνον ἀνατλῆναι, πάντα δὲ κίνδυνον ὑπομεῖναι τοῦ ἐπαινεῖσθαι ἕνεκα.

What does a beautiful leader look like? What effect does beauty have on leadership and leadership on beauty?οἱ δὲ Περσεῖδαι ἀπὸ Περσέως κλῄζονται: μητρὸς δὲ ὁμολογεῖται Μανδάνης γενέσθαι: ἡ δὲ Μανδάνη αὕτη Ἀστυάγους ἦν θυγάτηρ τοῦ Μήδων γενομένου βασιλέως. φῦναι δὲ ὁ Κῦρος λέγεται καὶ ᾁδεται ἔτι καὶ νῦν ὑπὸ τῶν βαρβάρων εἶδος μὲν κάλλιστος, ψυχὴν δὲ φιλανθρωπότατος καὶ φιλομαθέστατος καὶ φιλοτιμότατος, ὥστε πάντα μὲν πόνον ἀνατλῆναι, πάντα δὲ κίνδυνον ὑπομεῖναι τοῦ ἐπαινεῖσθαι ἕνεκα.

¶ 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2 10

2. Cyrus received a Persian education…

φύσιν μὲν δὴ τῆς μορφῆς καὶ τῆς ψυχῆς τοιαύτην ἔχων διαμνημονεύεται:  What should be the first consideration when drawing up a set of laws for a community?ἐπαιδεύθη γε μὴν ἐν Περσῶν νόμοις: οὗτοι δὲ δοκοῦσιν οἱ νόμοι ἄρχεσθαι τοῦ κοινοῦ ἀγαθοῦ ἐπιμελούμενοι οὐκ ἔνθενπερ ἐν ταῖς πλείσταις πόλεσιν ἄρχονται. αἱ μὲν γὰρ πλεῖσται πόλεις ἀφεῖσαι παιδεύειν ὅπως τις ἐθέλει τοὺς ἑαυτοῦ παῖδας, καὶ αὐτοὺς τοὺς πρεσβυτέρους ὅπως ἐθέλουσι διάγειν, ἔπειτα προστάττουσιν αὐτοῖς μὴ κλέπτειν μηδὲ ἁρπάζειν, μὴ βίᾳ εἰς οἰκίαν παριέναι, μὴ παίειν ὃν μὴ δίκαιον, μὴ μοιχεύειν, μὴ ἀπειθεῖν ἄρχοντι, καὶ τἆλλα τὰ τοιαῦτα ὡσαύτως: ἢν δέ τις τούτων τι παραβαίνῃ, ζημίαν αὐτοῖς ἐπέθεσαν.

What should be the first consideration when drawing up a set of laws for a community?ἐπαιδεύθη γε μὴν ἐν Περσῶν νόμοις: οὗτοι δὲ δοκοῦσιν οἱ νόμοι ἄρχεσθαι τοῦ κοινοῦ ἀγαθοῦ ἐπιμελούμενοι οὐκ ἔνθενπερ ἐν ταῖς πλείσταις πόλεσιν ἄρχονται. αἱ μὲν γὰρ πλεῖσται πόλεις ἀφεῖσαι παιδεύειν ὅπως τις ἐθέλει τοὺς ἑαυτοῦ παῖδας, καὶ αὐτοὺς τοὺς πρεσβυτέρους ὅπως ἐθέλουσι διάγειν, ἔπειτα προστάττουσιν αὐτοῖς μὴ κλέπτειν μηδὲ ἁρπάζειν, μὴ βίᾳ εἰς οἰκίαν παριέναι, μὴ παίειν ὃν μὴ δίκαιον, μὴ μοιχεύειν, μὴ ἀπειθεῖν ἄρχοντι, καὶ τἆλλα τὰ τοιαῦτα ὡσαύτως: ἢν δέ τις τούτων τι παραβαίνῃ, ζημίαν αὐτοῖς ἐπέθεσαν.

¶ 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3 14

3. The Persian system develops a moral character; the system begins with a “Free Square”…

οἱ δὲ Περσικοὶ νόμοι προλαβόντες ἐπιμέλονται ὅπως τὴν ἀρχὴν μὴ τοιοῦτοι ἔσονται οἱ πολῖται οἷοι πονηροῦ τινος ἢ αἰσχροῦ ἔργου ἐφίεσθαι. ἐπιμέλονται δὲ ὧδε. ἔστιν αὐτοῖς ἐλευθέρα ἀγορὰ καλουμένη, ἔνθα τά τε βασίλεια καὶ τἆλλα ἀρχεῖα πεποίηται. ἐντεῦθεν τὰ μὲν ὤνια καὶ οἱ ἀγοραῖοι καὶ αἱ τούτων φωναὶ καὶ ἀπειροκαλίαι ἀπελήλανται εἰς ἄλλον τόπον, ὡς μὴ μιγνύηται ἡ τούτων τύρβη τῇ τῶν πεπαιδευμένων εὐκοσμίᾳ.

¶ 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4 4

4. The square is divided into four parts, belonging to boys, adolescents, mature men, and elders…

διῄρηται δὲ αὕτη ἡ ἀγορὰ ἡ περὶ τὰ ἀρχεῖα τέτταρα μέρη: τούτων δ᾽ ἔστιν ἓν μὲν παισίν, ἓν δὲ ἐφήβοις, ἄλλο τελείοις ἀνδράσιν, ἄλλο τοῖς ὑπὲρ τὰ στρατεύσιμα ἔτη γεγονόσι. νόμῳ δ᾽ εἰς τὰς ἑαυτῶν χώρας ἕκαστοι τούτων πάρεισιν,  How does the Persian agoge resemble a modern university or boarding school?οἱ μὲν παῖδες ἅμα τῇ ἡμέρᾳ καὶ οἱ τέλειοι ἄνδρες, οἱ δὲ γεραίτεροι ἡνίκ᾽ ἂν ἑκάστῳ προχωρῇ, πλὴν ἐν ταῖς τεταγμέναις ἡμέραις, ἐν αἷς αὐτοὺς δεῖ παρεῖναι. οἱ δὲ ἔφηβοι καὶ κοιμῶνται περὶ τὰ ἀρχεῖα σὺν τοῖς γυμνητικοῖς ὅπλοις πλὴν τῶν γεγαμηκότων: οὗτοι δὲ οὔτε ἐπιζητοῦνται, ἢν μὴ προρρηθῇ παρεῖναι, οὔτε πολλάκις ἀπεῖναι καλόν.

How does the Persian agoge resemble a modern university or boarding school?οἱ μὲν παῖδες ἅμα τῇ ἡμέρᾳ καὶ οἱ τέλειοι ἄνδρες, οἱ δὲ γεραίτεροι ἡνίκ᾽ ἂν ἑκάστῳ προχωρῇ, πλὴν ἐν ταῖς τεταγμέναις ἡμέραις, ἐν αἷς αὐτοὺς δεῖ παρεῖναι. οἱ δὲ ἔφηβοι καὶ κοιμῶνται περὶ τὰ ἀρχεῖα σὺν τοῖς γυμνητικοῖς ὅπλοις πλὴν τῶν γεγαμηκότων: οὗτοι δὲ οὔτε ἐπιζητοῦνται, ἢν μὴ προρρηθῇ παρεῖναι, οὔτε πολλάκις ἀπεῖναι καλόν.

¶ 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5 3

5. Each division has twelve officers, corresponding to the 12 Persian tribes…

ἄρχοντες δ᾽ ἐφ᾽ ἑκάστῳ τούτων τῶν μερῶν εἰσι δώδεκα: δώδεκα γὰρ καὶ Περσῶν φυλαὶ διῄρηνται. καὶ ἐπὶ μὲν τοῖς παισὶν ἐκ τῶν γεραιτέρων ᾑρημένοι εἰσὶν οἳ ἂν δοκῶσι τοὺς παῖδας βελτίστους ἀποδεικνύναι: ἐπὶ δὲ τοῖς ἐφήβοις ἐκ τῶν τελείων ἀνδρῶν οἳ ἂν αὖ τοὺς ἐφήβους βελτίστους δοκῶσι παρέχειν: ἐπὶ δὲ τοῖς τελείοις ἀνδράσιν οἳ ἂν δοκῶσι παρέχειν αὐτοὺς μάλιστα τὰ τεταγμένα ποιοῦντας καὶ τὰ παραγγελλόμενα ὑπὸ τῆς μεγίστης ἀρχῆς: εἰσὶ δὲ καὶ τῶν γεραιτέρων προστάται ᾑρημένοι, οἳ προστατεύουσιν ὅπως καὶ οὗτοι τὰ καθήκοντα ἀποτελῶσιν. ἃ δὲ ἑκάστῃ ἡλικίᾳ προστέτακται ποιεῖν διηγησόμεθα, ὡς μᾶλλον δῆλον γένηται ᾗ ἐπιμέλονται ὡς ἂν βέλτιστοι εἶεν οἱ πολῖται.

¶ 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6 6

6. The boys learn justice by bringing charges against one another…

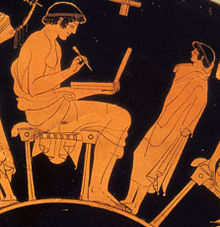

οἱ μὲν δὴ παῖδες εἰς τὰ διδασκαλεῖα φοιτῶντες διάγουσι μανθάνοντες δικαιοσύνην: καὶ λέγουσιν ὅτι ἐπὶ τοῦτο ἔρχονται ὥσπερ παρ᾽ ἡμῖν ὅτι γράμματα μαθησόμενοι.  How does the Persian education compare to the Greek?οἱ δ᾽ ἄρχοντες αὐτῶν διατελοῦσι τὸ πλεῖστον τῆς ἡμέρας δικάζοντες αὐτοῖς. γίγνεται γὰρ δὴ καὶ παισὶ πρὸς ἀλλήλους ὥσπερ ἀνδράσιν ἐγκλήματα καὶ κλοπῆς καὶ ἁρπαγῆς καὶ βίας καὶ ἀπάτης καὶ κακολογίας καὶ ἄλλων οἵων δὴ εἰκός.

How does the Persian education compare to the Greek?οἱ δ᾽ ἄρχοντες αὐτῶν διατελοῦσι τὸ πλεῖστον τῆς ἡμέρας δικάζοντες αὐτοῖς. γίγνεται γὰρ δὴ καὶ παισὶ πρὸς ἀλλήλους ὥσπερ ἀνδράσιν ἐγκλήματα καὶ κλοπῆς καὶ ἁρπαγῆς καὶ βίας καὶ ἀπάτης καὶ κακολογίας καὶ ἄλλων οἵων δὴ εἰκός.

¶ 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7 1

7. The boys bring one another to trial for lack of gratitude, which the Persians think most hateful…

οὓς δ᾽ ἂν γνῶσι τούτων τι ἀδικοῦντας, τιμωροῦνται. κολάζουσι δὲ καὶ ὃν ἂν ἀδίκως ἐγκαλοῦντα εὑρίσκωσι. δικάζουσι δὲ καὶ ἐγκλήματος οὗ ἕνεκα ἄνθρωποι μισοῦσι μὲν ἀλλήλους μάλιστα, δικάζονται δὲ ἥκιστα, ἀχαριστίας, καὶ ὃν ἂν γνῶσι δυνάμενον μὲν χάριν ἀποδιδόναι, μὴ ἀποδιδόντα δέ, κολάζουσι καὶ τοῦτον ἰσχυρῶς. οἴονται γὰρ τοὺς ἀχαρίστους καὶ περὶ θεοὺς ἂν μάλιστα ἀμελῶς ἔχειν καὶ περὶ γονέας καὶ πατρίδα καὶ φίλους. ἕπεσθαι δὲ δοκεῖ μάλιστα τῇ ἀχαριστίᾳ ἡ ἀναισχυντία: καὶ γὰρ αὕτη μεγίστη δοκεῖ εἶναι ἐπὶ πάντα τὰ αἰσχρὰ ἡγεμών.

¶ 8

Leave a comment on paragraph 8 17

8. The boys also learn self-control and self-mastery as well as how to shoot a bow and throw a spear…

διδάσκουσι δὲ τοὺς παῖδας καὶ σωφροσύνην: μέγα δὲ συμβάλλεται εἰς τὸ μανθάνειν σωφρονεῖν αὐτοὺς ὅτι καὶ τοὺς πρεσβυτέρους ὁρῶσιν ἀνὰ πᾶσαν ἡμέραν σωφρόνως διάγοντας.  How does the Cyropaedia compare with other works of literature that explore the experimentation with a ‘just society’ in childhood? διδάσκουσι δὲ αὐτοὺς καὶ πείθεσθαι τοῖς ἄρχουσι: μέγα δὲ καὶ εἰς τοῦτο συμβάλλεται ὅτι ὁρῶσι τοὺς πρεσβυτέρους πειθομένους τοῖς ἄρχουσιν ἰσχυρῶς.

How does the Cyropaedia compare with other works of literature that explore the experimentation with a ‘just society’ in childhood? διδάσκουσι δὲ αὐτοὺς καὶ πείθεσθαι τοῖς ἄρχουσι: μέγα δὲ καὶ εἰς τοῦτο συμβάλλεται ὅτι ὁρῶσι τοὺς πρεσβυτέρους πειθομένους τοῖς ἄρχουσιν ἰσχυρῶς.  How familiar was Xenophon with Persian weaponry? διδάσκουσι δὲ καὶ ἐγκράτειαν γαστρὸς καὶ ποτοῦ: μέγα δὲ καὶ εἰς τοῦτο συμβάλλεται ὅτι ὁρῶσι τοὺς πρεσβυτέρους οὐ πρόσθεν ἀπιόντας γαστρὸς ἕνεκα πρὶν ἂν ἀφῶσιν οἱ ἄρχοντες, καὶ ὅτι οὐ παρὰ μητρὶ σιτοῦνται οἱ παῖδες, ἀλλὰ παρὰ τῷ διδασκάλῳ, ὅταν οἱ ἄρχοντες σημήνωσι. φέρονται δὲ οἴκοθεν σῖτον μὲν ἄρτον, ὄψον δὲ κάρδαμον, πιεῖν δέ, ἤν τις διψῇ, κώθωνα, ὡς ἀπὸ τοῦ ποταμοῦ ἀρύσασθαι. πρὸς δὲ τούτοις μανθάνουσι καὶ τοξεύειν καὶ ἀκοντίζειν. μέχρι μὲν δὴ ἓξ ἢ ἑπτακαίδεκα ἐτῶν ἀπὸ γενεᾶς οἱ παῖδες ταῦτα πράττουσιν, ἐκ τούτου δὲ εἰς τοὺς ἐφήβους ἐξέρχονται.

How familiar was Xenophon with Persian weaponry? διδάσκουσι δὲ καὶ ἐγκράτειαν γαστρὸς καὶ ποτοῦ: μέγα δὲ καὶ εἰς τοῦτο συμβάλλεται ὅτι ὁρῶσι τοὺς πρεσβυτέρους οὐ πρόσθεν ἀπιόντας γαστρὸς ἕνεκα πρὶν ἂν ἀφῶσιν οἱ ἄρχοντες, καὶ ὅτι οὐ παρὰ μητρὶ σιτοῦνται οἱ παῖδες, ἀλλὰ παρὰ τῷ διδασκάλῳ, ὅταν οἱ ἄρχοντες σημήνωσι. φέρονται δὲ οἴκοθεν σῖτον μὲν ἄρτον, ὄψον δὲ κάρδαμον, πιεῖν δέ, ἤν τις διψῇ, κώθωνα, ὡς ἀπὸ τοῦ ποταμοῦ ἀρύσασθαι. πρὸς δὲ τούτοις μανθάνουσι καὶ τοξεύειν καὶ ἀκοντίζειν. μέχρι μὲν δὴ ἓξ ἢ ἑπτακαίδεκα ἐτῶν ἀπὸ γενεᾶς οἱ παῖδες ταῦτα πράττουσιν, ἐκ τούτου δὲ εἰς τοὺς ἐφήβους ἐξέρχονται.

¶ 9

Leave a comment on paragraph 9 2

9. The adolescents spend ten years passing the night in the Free Square in order to develop self-control, and serve the authorities as necessary…

οὗτοι δ᾽ αὖ οἱ ἔφηβοι διάγουσιν ὧδε. δέκα ἔτη ἀφ᾽ οὗ ἂν ἐκ παίδων ἐξέλθωσι κοιμῶνται μὲν περὶ τὰ ἀρχεῖα, ὥσπερ προειρήκαμεν, καὶ φυλακῆς ἕνεκα τῆς πόλεως καὶ σωφροσύνης: δοκεῖ γὰρ αὕτη ἡ ἡλικία μάλιστα ἐπιμελείας δεῖσθαι: παρέχουσι δὲ καὶ τὴν ἡμέραν ἑαυτοὺς τοῖς ἄρχουσι χρῆσθαι ἤν τι δέωνται ὑπὲρ τοῦ κοινοῦ. καὶ ὅταν μὲν δέῃ, πάντες μένουσι περὶ τὰ ἀρχεῖα: What role does sôphrosunê play in ‘The Godfather,’ especially in Michael (Cyrus?) and Sonny/Fredo (Cyaxares?)? ὅταν δὲ ἐξίῃ βασιλεὺς ἐπὶ θήραν, ἐξάγει τὴν ἡμίσειαν τῆς φυλακῆς: ποιεῖ δὲ τοῦτο πολλάκις τοῦ μηνός. ἔχειν δὲ δεῖ τοὺς ἐξιόντας τόξα καὶ παρὰ τὴν φαρέτραν ἐν κολεῷ κοπίδα ἢ σάγαριν, ἔτι δὲ γέρρον καὶ παλτὰ δύο, ὥστε τὸ μὲν ἀφεῖναι, τῷ δ᾽, ἂν δέῃ, ἐκ χειρὸς χρῆσθαι.

What role does sôphrosunê play in ‘The Godfather,’ especially in Michael (Cyrus?) and Sonny/Fredo (Cyaxares?)? ὅταν δὲ ἐξίῃ βασιλεὺς ἐπὶ θήραν, ἐξάγει τὴν ἡμίσειαν τῆς φυλακῆς: ποιεῖ δὲ τοῦτο πολλάκις τοῦ μηνός. ἔχειν δὲ δεῖ τοὺς ἐξιόντας τόξα καὶ παρὰ τὴν φαρέτραν ἐν κολεῷ κοπίδα ἢ σάγαριν, ἔτι δὲ γέρρον καὶ παλτὰ δύο, ὥστε τὸ μὲν ἀφεῖναι, τῷ δ᾽, ἂν δέῃ, ἐκ χειρὸς χρῆσθαι.

¶ 10

Leave a comment on paragraph 10 3

10. The hunt is paid for at public expense, because it is seen as the best preparation for war…

διὰ τοῦτο δὲ δημοσίᾳ τοῦ θηρᾶν ἐπιμέλονται, καὶ βασιλεὺς ὥσπερ καὶ ἐν πολέμῳ ἡγεμών ἐστιν αὐτοῖς καὶ αὐτός τε θηρᾷ καὶ τῶν ἄλλων ἐπιμελεῖται ὅπως ἂν θηρῶσιν, ὅτι ἀληθεστάτη αὐτοῖς δοκεῖ εἶναι αὕτη ἡ μελέτη τῶν πρὸς τὸν πόλεμον. How important is self-control in childhood for later success in life? καὶ γὰρ πρῲ ἀνίστασθαι ἐθίζει καὶ ψύχη καὶ θάλπη ἀνέχεσθαι, γυμνάζει δὲ καὶ ὁδοιπορίαις καὶ δρόμοις, ἀνάγκη δὲ καὶ τοξεῦσαι θηρίον καὶ ἀκοντίσαι ὅπου ἂν παραπίπτῃ. καὶ τὴν ψυχὴν δὲ πολλάκις ἀνάγκη θήγεσθαι ὅταν τι τῶν ἀλκίμων θηρίων ἀνθιστῆται: παίειν μὲν γὰρ δήπου δεῖ τὸ ὁμόσε γιγνόμενον, φυλάξασθαι δὲ τὸ ἐπιφερόμενον: ὥστε οὐ ῥᾴδιον εὑρεῖν τί ἐν τῇ θήρᾳ ἄπεστι τῶν ἐν πολέμῳ παρόντων.

How important is self-control in childhood for later success in life? καὶ γὰρ πρῲ ἀνίστασθαι ἐθίζει καὶ ψύχη καὶ θάλπη ἀνέχεσθαι, γυμνάζει δὲ καὶ ὁδοιπορίαις καὶ δρόμοις, ἀνάγκη δὲ καὶ τοξεῦσαι θηρίον καὶ ἀκοντίσαι ὅπου ἂν παραπίπτῃ. καὶ τὴν ψυχὴν δὲ πολλάκις ἀνάγκη θήγεσθαι ὅταν τι τῶν ἀλκίμων θηρίων ἀνθιστῆται: παίειν μὲν γὰρ δήπου δεῖ τὸ ὁμόσε γιγνόμενον, φυλάξασθαι δὲ τὸ ἐπιφερόμενον: ὥστε οὐ ῥᾴδιον εὑρεῖν τί ἐν τῇ θήρᾳ ἄπεστι τῶν ἐν πολέμῳ παρόντων.

¶ 11

Leave a comment on paragraph 11 9

11. The adolescents learn self-mastery over their appetite for food while on the hunt…

ἐξέρχονται δὲ ἐπὶ τὴν θήραν ἄριστον ἔχοντες πλέον μέν, ὡς τὸ εἰκός, τῶν παίδων, τἆλλα δὲ ὅμοιον. καὶ θηρῶντες μὲν οὐκ ἂν ἀριστήσαιεν, To what extent does a good hunter resemble a good leader? Compare Cyropaedia 1.4.7-10, 4.6.2-4 ἢν δέ τι δεήσῃ ἢ θηρίου ἕνεκα ἐπικαταμεῖναι ἢ ἄλλως ἐθελήσωσι διατρῖψαι περὶ τὴν θήραν, τὸ οὖν ἄριστον τοῦτο δειπνήσαντες τὴν ὑστεραίαν αὖ θηρῶσι μέχρι δείπνου, καὶ μίαν ἄμφω τούτω τὼ ἡμέρα λογίζονται, ὅτι μιᾶς ἡμέρας σῖτον δαπανῶσι. τοῦτο δὲ ποιοῦσι τοῦ ἐθίζεσθαι ἕνεκα, ἵν᾽ ἐάν τι καὶ ἐν πολέμῳ δεήσῃ, δύνωνται ταὐτὸ ποιεῖν.

To what extent does a good hunter resemble a good leader? Compare Cyropaedia 1.4.7-10, 4.6.2-4 ἢν δέ τι δεήσῃ ἢ θηρίου ἕνεκα ἐπικαταμεῖναι ἢ ἄλλως ἐθελήσωσι διατρῖψαι περὶ τὴν θήραν, τὸ οὖν ἄριστον τοῦτο δειπνήσαντες τὴν ὑστεραίαν αὖ θηρῶσι μέχρι δείπνου, καὶ μίαν ἄμφω τούτω τὼ ἡμέρα λογίζονται, ὅτι μιᾶς ἡμέρας σῖτον δαπανῶσι. τοῦτο δὲ ποιοῦσι τοῦ ἐθίζεσθαι ἕνεκα, ἵν᾽ ἐάν τι καὶ ἐν πολέμῳ δεήσῃ, δύνωνται ταὐτὸ ποιεῖν.  What are the health benefits of cardamon?

What are the health benefits of cardamon?

καὶ ὄψον δὲ τοῦτο ἔχουσιν οἱ τηλικοῦτοι ὅ τι ἂν θηράσωσιν: εἰ δὲ μή, τὸ κάρδαμον. εἰ δέ τις αὐτοὺς οἴεται ἢ ἐσθίειν ἀηδῶς, ὅταν κάρδαμον μόνον ἔχωσιν ἐπὶ τῷ σίτῳ, ἢ πίνειν ἀηδῶς, ὅταν ὕδωρ πίνωσιν, ἀναμνησθήτω πῶς μὲν ἡδὺ μᾶζα καὶ ἄρτος πεινῶντι φαγεῖν, πῶς δὲ ἡδὺ ὕδωρ πιεῖν διψῶντι.

¶ 12

Leave a comment on paragraph 12 4

12. The adolescents also engage in contests for prizes in the skills they learned as boys…

αἱ δ᾽ αὖ μένουσαι φυλαὶ διατρίβουσι μελετῶσαι τά τε ἄλλα ἃ παῖδες ὄντες ἔμαθον καὶ τοξεύειν καὶ ἀκοντίζειν, καὶ διαγωνιζόμενοι ταῦτα πρὸς ἀλλήλους διατελοῦσιν. εἰσὶ δὲ καὶ δημόσιοι τούτων ἀγῶνες καὶ ἆθλα προτίθεται: ἐν ᾗ δ᾽ ἂν τῶν φυλῶν πλεῖστοι ὦσι δαημονέστατοι καὶ ἀνδρικώτατοι καὶ εὐπιστότατοι, ἐπαινοῦσιν οἱ πολῖται καὶ τιμῶσιν οὐ μόνον τὸν νῦν ἄρχοντα αὐτῶν, ἀλλὰ καὶ ὅστις αὐτοὺς παῖδας ὄντας ἐπαίδευσε.  Tu pulmentaria quaere sudando!χρῶνται δὲ τοῖς μένουσι τῶν ἐφήβων αἱ ἀρχαί, ἤν τι ἢ φρουρῆσαι δεήσῃ ἢ κακούργους ἐρευνῆσαι ἢ λῃστὰς ὑποδραμεῖν ἢ καὶ ἄλλο τι ὅσα ἰσχύος ἢ τάχους ἔργα ἐστί. ταῦτα μὲν δὴ οἱ ἔφηβοι πράττουσιν. ἐπειδὰν δὲ τὰ δέκα ἔτη διατελέσωσιν, ἐξέρχονται εἰς τοὺς τελείους ἄνδρας.

Tu pulmentaria quaere sudando!χρῶνται δὲ τοῖς μένουσι τῶν ἐφήβων αἱ ἀρχαί, ἤν τι ἢ φρουρῆσαι δεήσῃ ἢ κακούργους ἐρευνῆσαι ἢ λῃστὰς ὑποδραμεῖν ἢ καὶ ἄλλο τι ὅσα ἰσχύος ἢ τάχους ἔργα ἐστί. ταῦτα μὲν δὴ οἱ ἔφηβοι πράττουσιν. ἐπειδὰν δὲ τὰ δέκα ἔτη διατελέσωσιν, ἐξέρχονται εἰς τοὺς τελείους ἄνδρας.

¶ 13

Leave a comment on paragraph 13 4

13. The adults serve the commonwealth as necessary for 25 years…

ἀφ᾽ οὗ δ᾽ ἂν ἐξέλθωσι χρόνου οὗτοι αὖ πέντε καὶ εἴκοσιν ἔτη διάγουσιν ὧδε. πρῶτον μὲν ὥσπερ οἱ ἔφηβοι παρέχουσιν ἑαυτοὺς ταῖς ἀρχαῖς χρῆσθαι, ἤν τι δέῃ ὑπὲρ τοῦ κοινοῦ, ὅσα φρονούντων τε ἤδη ἔργα ἐστὶ καὶ ἔτι δυναμένων. ἢν δέ ποι δέῃ στρατεύεσθαι, τόξα μὲν οἱ οὕτω πεπαιδευμένοι οὐκέτι ἔχοντες οὐδὲ παλτὰ στρατεύονται, τὰ δὲ ἀγχέμαχα ὅπλα καλούμενα, θώρακά τε περὶ τοῖς στέρνοις καὶ γέρρον ἐν τῇ ἀριστερᾷ, οἷόνπερ γράφονται οἱ Πέρσαι ἔχοντες,  What role does organized competition play in promoting excellence?ἐν δὲ τῇ δεξιᾷ μάχαιραν ἢ κοπίδα. καὶ αἱ ἀρχαὶ δὲ πᾶσαι ἐκ τούτων καθίστανται πλὴν οἱ τῶν παίδων διδάσκαλοι. ἐπειδὰν δὲ τὰ πέντε καὶ εἴκοσιν ἔτη διατελέσωσιν, εἴησαν μὲν ἂν οὗτοι πλέον τι γεγονότες ἢ τὰ πεντήκοντα ἔτη ἀπὸ γενεᾶς: ἐξέρχονται δὲ τηνικαῦτα εἰς τοὺς γεραιτέρους ὄντας τε καὶ καλουμένους.

What role does organized competition play in promoting excellence?ἐν δὲ τῇ δεξιᾷ μάχαιραν ἢ κοπίδα. καὶ αἱ ἀρχαὶ δὲ πᾶσαι ἐκ τούτων καθίστανται πλὴν οἱ τῶν παίδων διδάσκαλοι. ἐπειδὰν δὲ τὰ πέντε καὶ εἴκοσιν ἔτη διατελέσωσιν, εἴησαν μὲν ἂν οὗτοι πλέον τι γεγονότες ἢ τὰ πεντήκοντα ἔτη ἀπὸ γενεᾶς: ἐξέρχονται δὲ τηνικαῦτα εἰς τοὺς γεραιτέρους ὄντας τε καὶ καλουμένους.

¶ 14

Leave a comment on paragraph 14 3

14. The elders do not perform military service but serve as judges…

οἱ δ᾽ αὖ γεραίτεροι οὗτοι στρατεύονται μὲν οὐκέτι ἔξω τῆς ἑαυτῶν, οἴκοι δὲ μένοντες δικάζουσι τά τε κοινὰ καὶ τὰ ἴδια πάντα. καὶ θανάτου δὲ οὗτοι κρίνουσι, καὶ τὰς ἀρχὰς οὗτοι πάσας αἱροῦνται: καὶ ἤν τις ἢ ἐν ἐφήβοις ἢ ἐν τελείοις ἀνδράσιν ἐλλίπῃ τι τῶν νομίμων, φαίνουσι μὲν οἱ φύλαρχοι ἕκαστοι καὶ τῶν ἄλλων ὁ βουλόμενος, οἱ δὲ γεραίτεροι ἀκούσαντες ἐκκρίνουσιν: ὁ δὲ ἐκκριθεὶς ἄτιμος διατελεῖ τὸν λοιπὸν βίον.

¶ 15

Leave a comment on paragraph 15 5

15. All Persian nobles may attend the schools, but must pass each course to advance to the next stage…

ἵνα δὲ σαφέστερον δηλωθῇ πᾶσα ἡ Περσῶν πολιτεία, μικρὸν ἐπάνειμι: νῦν γὰρ ἐν βραχυτάτῳ ἂν δηλωθείη διὰ τὰ προειρημένα. λέγονται μὲν γὰρ Πέρσαι ἀμφὶ τὰς δώδεκα μυριάδας εἶναι: τούτων δ᾽ οὐδεὶς ἀπελήλαται νόμῳ τιμῶν καὶ ἀρχῶν, ἀλλ᾽ ἔξεστι πᾶσι Πέρσαις πέμπειν τοὺς ἑαυτῶν παῖδας εἰς τὰ κοινὰ τῆς δικαιοσύνης διδασκαλεῖα.  What is the relationship between access to education and the well-being of a community?ἀλλ᾽ οἱ μὲν δυνάμενοι τρέφειν τοὺς παῖδας ἀργοῦντας πέμπουσιν, οἱ δὲ μὴ δυνάμενοι οὐ πέμπουσιν. οἳ δ᾽ ἂν παιδευθῶσι παρὰ τοῖς δημοσίοις διδασκάλοις, ἔξεστιν αὐτοῖς ἐν τοῖς ἐφήβοις νεανισκεύεσθαι, τοῖς δὲ μὴ διαπαιδευθεῖσιν οὕτως οὐκ ἔξεστιν. οἳ δ᾽ ἂν αὖ ἐν τοῖς ἐφήβοις διατελέσωσι τὰ νόμιμα ποιοῦντες, ἔξεστι τούτοις εἰς τοὺς τελείους ἄνδρας συναλίζεσθαι καὶ ἀρχῶν καὶ τιμῶν μετέχειν, οἳ δ᾽ ἂν μὴ διαγένωνται ἐν τοῖς ἐφήβοις, οὐκ εἰσέρχονται εἰς τοὺς τελείους. οἳ δ᾽ ἂν αὖ ἐν τοῖς τελείοις διαγένωνται ἀνεπίληπτοι, οὗτοι τῶν γεραιτέρων γίγνονται. οὕτω μὲν δὴ οἱ γεραίτεροι διὰ πάντων τῶν καλῶν ἐληλυθότες καθίστανται: καὶ ἡ πολιτεία αὕτη, ᾗ οἴονται χρώμενοι βέλτιστοι ἂν εἶναι.

What is the relationship between access to education and the well-being of a community?ἀλλ᾽ οἱ μὲν δυνάμενοι τρέφειν τοὺς παῖδας ἀργοῦντας πέμπουσιν, οἱ δὲ μὴ δυνάμενοι οὐ πέμπουσιν. οἳ δ᾽ ἂν παιδευθῶσι παρὰ τοῖς δημοσίοις διδασκάλοις, ἔξεστιν αὐτοῖς ἐν τοῖς ἐφήβοις νεανισκεύεσθαι, τοῖς δὲ μὴ διαπαιδευθεῖσιν οὕτως οὐκ ἔξεστιν. οἳ δ᾽ ἂν αὖ ἐν τοῖς ἐφήβοις διατελέσωσι τὰ νόμιμα ποιοῦντες, ἔξεστι τούτοις εἰς τοὺς τελείους ἄνδρας συναλίζεσθαι καὶ ἀρχῶν καὶ τιμῶν μετέχειν, οἳ δ᾽ ἂν μὴ διαγένωνται ἐν τοῖς ἐφήβοις, οὐκ εἰσέρχονται εἰς τοὺς τελείους. οἳ δ᾽ ἂν αὖ ἐν τοῖς τελείοις διαγένωνται ἀνεπίληπτοι, οὗτοι τῶν γεραιτέρων γίγνονται. οὕτω μὲν δὴ οἱ γεραίτεροι διὰ πάντων τῶν καλῶν ἐληλυθότες καθίστανται: καὶ ἡ πολιτεία αὕτη, ᾗ οἴονται χρώμενοι βέλτιστοι ἂν εἶναι.

¶ 16

Leave a comment on paragraph 16 3

16. Contemporary Persian habits reflect this training

καὶ νῦν δὲ ἔτι ἐμμένει μαρτύρια καὶ τῆς μετρίας διαίτης αὐτῶν καὶ τοῦ ἐκπονεῖσθαι τὴν δίαιταν. αἰσχρὸν μὲν γὰρ ἔτι καὶ νῦν ἐστι Πέρσαις καὶ τὸ πτύειν καὶ τὸ ἀπομύττεσθαι καὶ τὸ φύσης μεστοὺς φαίνεσθαι, αἰσχρὸν δέ ἐστι καὶ τὸ ἰόντα ποι φανερὸν γενέσθαι ἢ τοῦ οὐρῆσαι ἕνεκα ἢ καὶ ἄλλου τινὸς τοιούτου. ταῦτα δὲ οὐκ ἂν ἐδύναντο ποιεῖν, εἰ μὴ καὶ διαίτῃ μετρίᾳ ἐχρῶντο καὶ τὸ ὑγρὸν ἐκπονοῦντες ἀνήλισκον, ὥστε ἄλλῃ πῃ ἀποχωρεῖν. ταῦτα μὲν δὴ κατὰ πάντων Περσῶν ἔχομεν λέγειν: οὗ δ᾽ ἕνεκα ὁ λόγος ὡρμήθη, νῦν λέξομεν τὰς Κύρου πράξεις ἀρξάμενοι ἀπὸ παιδός.

πατρὸς: What is Xenophon’s source for the attribution of Cyrus’ paternity to Cambyses? How likely is it that Cambyses was his father (and that the historical Cyrus was descended from royalty)?

InHerodotus Histories Cyrus’ father is Cambyses. In Ctesias F8d*3 he is Atradates. See Drews 1974 for the folk tradition of the “king from humble origins” dating back to Sargon of Akkad.

Moreover, (also in Ctesias) Cyrus’ mother is called Argoste in formulaic language that resembles Xenophon’s here (cf. Ἦν δὲ ὁ Κῦρος του Ἀτραδάτου παῖς, ὅστις ἐλῄστευεν ὑπὸ πενίας.Nicolaus of Damascus /Ctesias F*8.3 ). Why does Xenophon assert that there is agreement (ὁμολογεῖται) as to who Cyrus’ mother is?

Ἡ δὲ γυνὴ αὐτοῦ, Ἀργόστη ὄνομα, ἡ Κύρου μήτηρ, αἰπολοῦσα ἔζη,

Also an Old Persian inscription from Pasargadae (CMb ) says that Cyrus is the son of king Cambyses. I believe there is controversy about whether Cyrus or Darius is responsible for this, but either way it reflects a contemporary or near-contemporary Persian tradition.

Do you have a guess as to why Xenophon would claim here that there is “agreement” about Cyrus’ descent from Mandane? Presumably he has readCtesias ‘ account.

This is a small point, but I think the word choice may be important. Although both ὁμολογεῖται and λέγεται are ways to cite authorities without naming them, ὁμολογεῖται is highly marked. (ὁμολογεῖται is used in this sense only here in the Cyropaedia and rarely elsewhere in Xenophon, but λέγεται is quite common). Presuming that Xenophon had readCtesias ‘ account, do you think that he could be correcting him?

Good distinction between legetai and homologeitai. There is reason for believing that part of what Xenophon means to do with his account of Cyrus is to “correct” or “explain” other versions.Gera 1993:156-157 suggests that the Sacas-story in Cyropaedia 1.3 and Cyropaedia 1.4 may be correcting Ctesias Persica account of Cyrus-as-cupbearer. Similarly, we could see Xenophon as correcting Herodotus’ account of Cyrus among the Medes (especially what it means to “play at king” from an early age) with his much more cooperative account of Cyrus with his age-mates and Cyaxares in Cyropaedia 1.4 (I talk about this much more in my forthcoming book (Sandridge 2012 ), out this September, Loving Humanity, Learning, and Being Honored).

While I certainly see some validity to this approach, I have my doubts that that’s what Xenophon is trying to do. For one, I’m not really convinced that he expected his audience to know their Ctesias or even their Herodotus in great detail (though some readers surely would have). That of course doesn’t preclude him from trying to prevent any previous accounts from ever gaining reception. Because Xenophon seems so uninterested in getting a true historical account of Cyrus elsewhere in his work (which is not to say that he wasn’t using any sources for Cyrus), it seems likelier to me that he is just trying to give his story the veneer of historical accuracy, especially given the fact that he concludes the previous sub-chapter (Cyropaedia 1.1.6 ) by claiming to have done lots of research on Cyrus.

TheCyrus Cylinder, line 21 – an Akkadian document presumably drafted on Cyrus’s orders and recounting the conquest of Babylon – says that Cyrus was the son of Cambyses, the king of Anshan.

κάλλιστος: What did Xenophon think Cyrus looked like? What did the historical Cyrus look like?

Note the frequency in the later biographical tradition (e.g.Plutarch or Suetonius ) of answering that sort of question. In the “historical fiction” of Dares the Phrygian 12ff. , the details of the physical appearance of the various Greek heroes are invented, partly because there seems to have been an interest in this question, and partly to give credibility to the claim that this is an “eyewitness” account.

At least in Plutarch there is a tendency to see a person’s character in their appearance (cf. Alexander).

Xenophon says at one point that Cyrus had a large build (megethos), but as well as I can recall, that’s it. The most we can ascertain of his beauty is that it can make people fall in love with him (Artabazus) and make people jealous (cf. Tigranes’ jealous question to his wife inCyropaedia 3.1 ). It is as if Xenophon is more interested in characterizing his beauty like Helen’s in Book Three of the Iliad, namely by the effect it has on others. I am forgetting at the moment if Xenophon says anything more about Cyrus’ appearance when he takes on the Medan style of dress (I think he says the takes the high-heel shoes to make himself appear taller).

Cyrus does notice the beauty of others. When asked in <em>Cyropaedia 1.3 who is more beautiful his Persian father Cambyses or his Medan grandfather Astyages, he claims that they both are, in their own ways.

Is this somewhere where Xenophon is on the cusp of departing from his earlier Greek historian peers? We hear very little about the appearance of historical actors in Thucydides, for example, even Alcibiades. On the other hand, Plato often describes the appearance of Socrates’ interlocutors (for example, Theaetetus at the start ofPlato Theaetetus ) and their physical features become part of the discussion (Simmias and Cebes in Plato Phaedo ). The equation of physical and moral beauty is certainly more apparent in philosophical than historical texts at the time when Xenophon was probably writing. Alcibiades’ beauty may not be evident from his speeches and actions in Thucydides Histories 6.9-23 (e.g., the Sicilian expedition debate), but it is inescapable in his dramatic entrance at Plato Symposium 212c3-215a3 .

Could one assume that the ancient Persians look like their modern equivalents, or has there been a significant migration of peoples in the area?

Plutarch says that Cyrus was hawk-nosed: “The Persians affect such as are hawk-nosed and think them most beautiful, because Cyrus, the most beloved of their kings, had a nose of that shape” (Πέρσαι τῶν γρυπῶν ἐρῶσι καὶ καλλίστους ὑπολαμβάνουσι διὰ τὸ Κῦρον ἀγαπηθέντα μάλιστα τῶν βασιλέων γεγονέναι γρυπὸν τὸ εἶδος, Plutarch Moralia, Remarkable Sayings of Kings and Great Commanders 172E4-6, translation Goodwin; cf. also Πέρσαι δ’, ὅτιγρυπὸς ἦν ὁ Κῦρος, ἔτι καὶ νῦν ἐρῶσι τῶν γρυπῶν καὶ καλλίστους ὑπολαμβάνουσιν,Plutarch Moralia, Political Precepts 821F1-2 ). Perhaps coincidentally, Cyrus himself describes Chrysantas as having this type of nose (the only such mention of a hook-nose in all of Xenophon), offering to pair him with a snub-nosed woman so that they complement one another (Cyropaedia 8.4.21 ; cf. Plutarch Moralia 633B11-C1 , What, as Xenophon Intimates, are the most agreeable questions and most pleasant raillery at entertainment?).

φιλανθρωπότατος: What does Xenophon mean by this term?

On this see now Norman’s own Sandridge 2012.

φιλομαθέστατος: What does Xenophon mean by this term?

Is the character of Zal in the Shahnameh (p. 68 in Dick Davis’ translation) a possible cognate with Cyrus as a leader who loves to learn?

Note that Ctesias’ Cyrus (Ctesias F8d*1–7 ) has something of an “aptitude for learning” in that he progresses from gardener to lamp-bearer to Astyages’ personal cup-bearer.

φιλοτιμότατος: What does Xenophon mean by this term?

πάντα μὲν πόνον … πάντα δὲ κίνδυνον: What is this significance of a willingness to do all labors and take all risks for Xenophon’s Theory of Leadership?

This reminds us of the Alexander tradition, in which he is always the first over the wall, or the tale about him emptying his canteen (citation?) when his men have no water…is this simply part of a cultural definition of leaderly behavior, or could there be a definite line of influence/imitation here?

Both of those anecdotes come from Plutarch, I believe. There is a similar contemporary instance of Isocrates’ Evagoras leading the charge in his home-city of Salamis to reclaim his throne. As well as I can tell Cyrus’ philokindunia does not seem to be of this kind except in his youth (rushing into the hunt or the skirmish against the Assyrians). At the onset of one of the battles, he does get a little ahead of himself, but nothing comes of it. It is the recklessly bold prince of the Cadusians who pursues the fleeing Armenians or Abradatas charging his chariot into the Egyptians who exhibit this kind of all-out risk-taking (and they both die; the Hyrcanian is even a “lesson” in cutting out ahead of the pack).

It is worth thinking more carefully about what Cyrus’ “risking it all” actually means. He seems willing at least to “risk” all of his personal resources to pursue his ambitions.

In general it is a real dilemma for a leader to be “first” in battle and yet live long enough to manage the safety of the followers. Isocrates counsels Philip of Macedon against an “unseasonable philotimia” in risking himself too much in battle. I don’t know how far back this dilemma goes. No one in the Iliad (that I can recall) seems to worry what the ramifications would be if Agamemnon or Menelaus were killed in battle. Accordingly to Achilles’ criticism of him inIliad 1 , Agamemnon hangs back and hoards prizes whereas he should be fighting (as he does in Iliad 11 ).

Undertaking all toils is the mark of the leader. It seems that Xenophon’s peculiarity lies in the fact that he distinguishes between the supreme toils, undertaken only by leaders and inferior ones, undertaken by the idiotai (cf.Cyropaedia 1.6.8 , Cyropaedia 1.6.21 , Cyropaedia 1.6.25 ). Toils thus are inscribed in a set of hierarchical relations that can be observed throughout the Cyropaedia.

For Xenophon, the premier example of (reckless) daring in a leader would have been the younger Cyrus at the battle of Cunaxa, as recounted in the Anabasis, which got the Greeks into a heap of trouble. This gets us into the question of whether Xenophon at least partly modeled his depiction of Cyrus the Great on his namesake, the prince whom Xenophon followed into the heart of the Empire. A long time ago I made the case for that (Hirsch 1985:72-75 , The Friendship of the Barbarians), and further argued that the younger Cyrus created a propaganda campaign to justify his attempt to seize the throne, in which he equated himself with the founder of the Empire, and that this colored Xenophon’s representation of Cyrus the Great in the Cyropaedia.

On this point about what it means exactly for Cyrus to “risk it all”, I think you are right that Cyrus the Younger certainly goes beyond the sensible limit of this Xenophon’s proscription. As far as I can tell, Cyrus the Elder does not show much of a tendency toward reckless daring beyond his youth, both in the hunt (Cyropaedia 1.4.8 ) and in the first skirmish with the Assyrians (Cyropaedia 1.4.22 , Cyropaedia 1.4.24 ). He once later advances impulsively in battle, to no consequence (Cyropaedia 3.3.62 ), but otherwise reckless (and we might say “heroic”) daring is assigned to Cyrus’ followers, e.g., Abradatas (Cyropaedia 7.3.14-16 ) and the prince of the Cadusians (Cyropaedia 5.4.16 ). Farber 1979:505 notes that in Hellenistic inscriptions it is more often the followers than kings themselves that are praised for having philotimia. If philotimia does encourage risky behavior, Xenophon and later theorists of Hellenistic kingship may have downplayed it for this reason.

Steven, for what it’s worth, SimoParpola 2003:350 also argues that Xenophon modeled his hero on Cyrus the Younger, as suggested by a biographical sketch of the latter at Anabasis 1.9.2-28 , which “reads like an abbreviated Cyropaedia.” For Parpola, making Cyrus the Younger a source for much of the material in the Cyropaedia accounts for the accuracy of many of the details about Persian government and so on. Parpola does not, however, cite your book (Hirsch 1985 ).

The story about Alexander pouring out water in front of his troops also comes fromArrian Anabasis of Alexander 6.26 .It seems to me that this is Xenophon’s attempt at setting a Greek standard for the type of characteristics typical of a great leader. Similarly, Alexander’s biographers (such as Arrian) set him up as an exemplar of leadership, who the Romans looked to as an ideal leader. I think it is interesting to think of this kind of description as a tradition, which was crucial to the image of a successful leader, and also a tradition that continued across cultures.I have seen this type of leader standard in early ancient near eastern art. For example, the stele of Naram-Sin portrays the king as a warrior king, endowed with kuzbu (sexual allure). See I. Winter 1996 , “Sex,Rhetoric, and the Public Monument,” in (ed.) Kampen, Sexuality in Ancient Art. I know Naram-Sin is an early example, but the aspects of kingship, leadership, etc., as described in this passage, can also be found in later depictions of Assyrian and Achaemenid kings. So imitation seems to follow a standard of leadership previously established.

Yes, this is certainly true. Now we have to decide whether or not we view it as important simply that this is a literary motif, or if it is worth our time to try to distinguish what was ACTUALLY characteristic of Alexander’s behavior with relation to Cyrus. For instance, is Alexander’s treatment of Sisygambis inDiodorus 17.37.5 , Curtius 3.12.17 and Arrian 2.12.31 . Arrian’s way to evoke Cyropaedia 7.3.8-16 or did Alexander act this way towards her BECAUSE of the way Cyrus treated Pantheia in the Xenophon passage? Is this important or are we just mincing words? The idea of folk tradition leads me to think about Semiramis, the mythical founder of Babylon. I won’t venture to guess who she actually was, but she exhibits qualities in the Greek authors that make her almost “manly” (a good source for this is “Semiramis in History and Legend,” in (ed. E. Gruen 2005:11-22 ) Cultural Borrowings and Ethnic Appropriations in Antiquity, Franz Steiner Verlag (2005), 11-22) though I would also suggest caution when reading this article. But the ideas are interesting, though one might be led to wonder what we can believe, after all, when distinguishing between authorial interpretation and actual fact. I like to think, given the similarities between Cyrus’ stated objective in the Cylinder (a “historical”? document) and those in the Cyropaedia that Xenophon may have been dealing with a more factual Cyrus than we typically allow. And it is my preference, given Alexander’s extensive education in Persian culture (wither prior to his arrival via Aristotle or afterwards due to local exposure) to believe that he did many things the way he did because he wanted to act like Cyrus. We should remember that we have copies of the Bisitun inscription from places all over the empire (e.g. Elephantine), so texts like the Cyrus Cylinder may very well have made their way into Alexander’s hands.

Cyrus gives a similar formulation of how the love of praise can lead to great toil and risk-taking in a speech to his Persian peers as they set out to join the Medan campaign against the Assyrians (cf. ἐπαινούμενοι γὰρ μᾶλλον ἢ τοῖς ἄλλοις ἅπασι χαίρετε. τοὺς δ᾽ ἐπαίνου ἐραστὰς ἀνάγκη διὰ τοῦτο πάντα μὲν πόνον, πάντα δὲ κίνδυνον ἡδέως ὑποδύεσθαι,Cyropaedia 1.5.12 ). Thus loving praise is not only a desirable quality in leaders but also followers.

τοῦ ἐπαινεῖσθαι ἕνεκα: What is the significance of praise in Xenophon’s Theory of Leadership? To what extent does Xenophon distinguish it from flattery?

ὁ Κῦρος: Why is Cyrus referred to here with a definite article, whereas there was no definite article in the previous chapter (where he is mentioned three times)?

What is the significance of Cyrus’ beauty? What are its erotic implications? Does it signify noble birth? What role does it play in Cyrus’ leadership, for better or worse?

Cf.Xenophon Symposium 1.9 and Isocrates Evagoras 22 . One assumption seems to be that beautiful leaders inspire their followers with a feeling of eros, and an attendant desire to please the leader, which may be seen as a good thing; but that eros can compel a follower to flatter or otherwise corrupt a leader, who thus needs self-restraint (sophrosune) as a safeguard.

Cf. alsoXenophon Symposium 4.15–18 .

AtCyropaedia 1.4.27–28 a Medan man, later identified as Artabazus, falls in love with Cyrus. At Cyropaedia 4.1.22-23 Artabazus affirms his devotion to Cyrus and vows to help him enlist other Medes in the continuing campaign against the Assyrians. At Cyropaedia 3.1.41 Tigranes is envious of Cyrus’ beauty, fearing that he may have caught the attention of Tigranes’ new wife.

λέγεται καὶ ᾁδεται: What is the tradition of celebrating the Persian king in song? #folklore

SeeAthenaeus 14.633d–e and Strabo 15.3.18 .

See alsoGera 1993:13-22 , especially Gera 1993:16 .

The coordination recurs later in the book,Cyropaedia 1.4.25 . There it becomes more specific, as it is this good repute which impacts directly Cyrus’ relationship with Astyages and Cambyses. Further, the mention there of Cyrus’ good repute follows directly on the fact that Astyages didn’t know what to say (Cyropaedia 1.4.24 : οὐκ ἔχων…) about Cyrus’ deeds. This silence is, in turn, contrasted with Cyrus’ boasting over the conquered foes.

ἔτι καὶ νῦν: This phrase and its variants are regular in describing lasting institutions and foundations. This is the first such usage in the work. How is it used here?

This phrase is used later of customs (Cyropaedia 1.3.2 of Persian clothing, Cyropaedia 1.4.27 of the custom of kissing on the lips, Cyropaedia 1.6.33 on a ῥήτρα passed which requires teaching boys to tell the truth), but this first usage of the phrase in the work seems to require that sense that something that is done “still even now” is a law or custom or ordinance. It may be then that the practice of speech and song about Cyrus is performed like a custom and Xenophon is being hyperbolic. Or, perhaps, Xenophon here reflects the fact that praise of Cyrus was regularly given at certain types of commemorative events.

The phrase ἔτι καὶ νῦν and its variants (ἔτι καὶ ἐς ἐμέ) is also often used byHerodotus Histories . Does Xenophon build upon this historiographical tradition?

That’s an interesting question. I think that Xenophon, like his predecessors Hedodotus and Ctesias, had a challenge of linking events in the distant past to his own day, and in convincing their audience to believe them. But then again, its not clear how much of Cyropaedia Xenophon intended to be read as historical fact. A TLG search reveals some examples likeHerodotus Histories 2.135 οἳ καὶ νῦν ἔτι συννενέαται ὄπισθε μὲν τοῦ βωμοῦ τὸν Χῖοι ἀνέθεσαν, ἀντίον δὲ αὐτοῦ τοῦ νηοῦ. (I think this is the story of Rhodopis the Egyptian courtesan who donated iron spits to Delphi “and even now they are piled there”) and Herodotus Histories 2.99 (where Min built a dam to divert the Nile from Memphis, and even now the Persians watch this dam) and Herodotus Histories 1.185 (queen Nitocris made the Euphrates wind, and even now a traveller will notice this) and Herodotus Histories 4.166 (Aryandas, Darius’ satrap of Egypt, issued pure silver “and today the purest silver is Aryandic”).

οἱ δὲ Περσεῖδαι ἀπὸ Περσέως κλῄζονται: What is the history of the “Perseidai from Perseus” etymology? Does his choice of verb suggest anything about his source?

That should be “Perseidai from Perseus” sorry (although I think the Persai/Perseus connection is attested elsewhere). While this etymology is obvious, ScottNoegel has pointed out that the idea that similar words are fundamentally linked is first attested in Bronze Age Southwest Asia.

For what it’s worth, I wrote a fair amount about this in my book (Patterson 2010 , Kinship Myth). I don’t have page numbers at hand, but it was in the chapter on Herodotus Histories 7.150 , about Xerxes’ overtures to Argos. The link is attested in Herodotus, Hellanicus, and of course Aeschylus’ Persians. Hecataeus may have dealt with it as well (if not invented it), but no surviving fragments attest to that.

Why does Zonaras (fl. 12th cent. CE) translate Cyrus’ three superlative traits as ἀνδρειότατός τε καὶ σωφρονέστατος νουνεχής τε καὶ δικαιότατος (<em>Epitome Historiarum 1.224.28-29 )? #reception

The context of the passage in Zonaras clearly demonstrates that he is reading the Cyropaedia (and he alludes to Xenophon). The rest of the passage is a fairly faithful summary or translation, but he does not seem to have made much of an effort to capture κάλλιστος…φιλανθρωπότατος… φιλομαθέστατος…φιλοτιμότατος.

This is for students of Greek mythology: Why is it important that Cyrus’ lineage be traced back to the hero Perseus? Who is Perseus? What relationship between the Persians and Greeks is established through this link?

And a follow-up: If Cyrus receives a Persian education (rather than a Greek education), what might he have learned about the hero Perseus?