Chapter 1.1: The Problem of Ruling Humans and the Solution of Cyrus

¶ 1

Leave a comment on paragraph 1 41

1. Forms of government are difficult to maintain…

ἔννοιά ποθ᾽ ἡμῖν ἐγένετο ![]() ὅσαι δημοκρατίαι κατελύθησαν ὑπὸ τῶν ἄλλως πως

ὅσαι δημοκρατίαι κατελύθησαν ὑπὸ τῶν ἄλλως πως  Who was Xenophon the Athenian?βουλομένων πολιτεύεσθαι μᾶλλον ἢ ἐν δημοκρατίᾳ, ὅσαι τ᾽ αὖ μοναρχίαι, ὅσαι τε ὀλιγαρχίαι ἀνῄρηνται ἤδη ὑπὸ δήμων, καὶ ὅσοι τυραννεῖν ἐπιχειρήσαντες οἱ μὲν αὐτῶν καὶ ταχὺ πάμπαν κατελύθησαν, οἱ δὲ κἂν ὁποσονοῦν χρόνον ἄρχοντες διαγένωνται, θαυμάζονται ὡς σοφοί τε καὶ εὐτυχεῖς ἄνδρες γεγενημένοι. πολλοὺς δ᾽ ἐδοκοῦμεν καταμεμαθηκέναι καὶ ἐν ἰδίοις οἴκοις τοὺς μὲν ἔχοντας καὶ πλείονας οἰκέτας, τοὺς δὲ καὶ πάνυ ὀλίγους, καὶ ὅμως οὐδὲ τοῖς ὀλίγοις τούτοις πάνυ τι δυναμένους χρῆσθαι πειθομένοις τοὺς δεσπότας.

Who was Xenophon the Athenian?βουλομένων πολιτεύεσθαι μᾶλλον ἢ ἐν δημοκρατίᾳ, ὅσαι τ᾽ αὖ μοναρχίαι, ὅσαι τε ὀλιγαρχίαι ἀνῄρηνται ἤδη ὑπὸ δήμων, καὶ ὅσοι τυραννεῖν ἐπιχειρήσαντες οἱ μὲν αὐτῶν καὶ ταχὺ πάμπαν κατελύθησαν, οἱ δὲ κἂν ὁποσονοῦν χρόνον ἄρχοντες διαγένωνται, θαυμάζονται ὡς σοφοί τε καὶ εὐτυχεῖς ἄνδρες γεγενημένοι. πολλοὺς δ᾽ ἐδοκοῦμεν καταμεμαθηκέναι καὶ ἐν ἰδίοις οἴκοις τοὺς μὲν ἔχοντας καὶ πλείονας οἰκέτας, τοὺς δὲ καὶ πάνυ ὀλίγους, καὶ ὅμως οὐδὲ τοῖς ὀλίγοις τούτοις πάνυ τι δυναμένους χρῆσθαι πειθομένοις τοὺς δεσπότας.

¶ 2

Leave a comment on paragraph 2 15

2. While many animals are easy to herd, humans regularly resist authority…

ἔτι δὲ πρὸς τούτοις ἐνενοοῦμεν ὅτι ἄρχοντες μέν εἰσι καὶ οἱ βουκόλοι τῶν βοῶν καὶ οἱ ἱπποφορβοὶ τῶν ἵππων, καὶ πάντες δὲ οἱ καλούμενοι νομεῖς ὧν ἂν ἐπιστατῶσι ζῴων  How do herdsmen resemble rulers?εἰκότως ἂν ἄρχοντες τούτων νομίζοιντο· πάσας τοίνυν ταύτας τὰς ἀγέλας ἐδοκοῦμεν ὁρᾶν μᾶλλον ἐθελούσας πείθεσθαι τοῖς νομεῦσιν ἢ τοὺς ἀνθρώπους τοῖς ἄρχουσι. πορεύονταί τε γὰρ αἱ ἀγέλαι ᾗ ἂν αὐτὰς εὐθύνωσιν οἱ νομεῖς, νέμονταί τε χωρία ἐφ᾽ ὁποῖα ἂν αὐτὰς ἐπάγωσιν, ἀπέχονταί τε ὧν ἂν αὐτὰς ἀπείργωσι· καὶ τοῖς καρποῖς τοίνυν τοῖς γιγνομένοις ἐξ αὐτῶν ἐῶσι τοὺς νομέας χρῆσθαι οὕτως ὅπως ἂν αὐτοὶ βούλωνται. ἔτι τοίνυν οὐδεμίαν πώποτε ἀγέλην ᾐσθήμεθα συστᾶσαν ἐπὶ τὸν νομέα οὔτε ὡς μὴ πείθεσθαι οὔτε ὡς μὴ ἐπιτρέπειν τῷ καρπῷ χρῆσθαι, ἀλλὰ καὶ χαλεπώτεραί εἰσιν αἱ ἀγέλαι πᾶσι τοῖς ἀλλοφύλοις ἢ τοῖς ἄρχουσί τε καὶ ὠφελουμένοις ἀπ᾽ αὐτῶν· ἄνθρωποι δὲ ἐπ᾽ οὐδένας μᾶλλον συνίστανται ἢ ἐπὶ τούτους οὓς ἂν αἴσθωνται ἄρχειν αὑτῶν ἐπιχειροῦντας.

How do herdsmen resemble rulers?εἰκότως ἂν ἄρχοντες τούτων νομίζοιντο· πάσας τοίνυν ταύτας τὰς ἀγέλας ἐδοκοῦμεν ὁρᾶν μᾶλλον ἐθελούσας πείθεσθαι τοῖς νομεῦσιν ἢ τοὺς ἀνθρώπους τοῖς ἄρχουσι. πορεύονταί τε γὰρ αἱ ἀγέλαι ᾗ ἂν αὐτὰς εὐθύνωσιν οἱ νομεῖς, νέμονταί τε χωρία ἐφ᾽ ὁποῖα ἂν αὐτὰς ἐπάγωσιν, ἀπέχονταί τε ὧν ἂν αὐτὰς ἀπείργωσι· καὶ τοῖς καρποῖς τοίνυν τοῖς γιγνομένοις ἐξ αὐτῶν ἐῶσι τοὺς νομέας χρῆσθαι οὕτως ὅπως ἂν αὐτοὶ βούλωνται. ἔτι τοίνυν οὐδεμίαν πώποτε ἀγέλην ᾐσθήμεθα συστᾶσαν ἐπὶ τὸν νομέα οὔτε ὡς μὴ πείθεσθαι οὔτε ὡς μὴ ἐπιτρέπειν τῷ καρπῷ χρῆσθαι, ἀλλὰ καὶ χαλεπώτεραί εἰσιν αἱ ἀγέλαι πᾶσι τοῖς ἀλλοφύλοις ἢ τοῖς ἄρχουσί τε καὶ ὠφελουμένοις ἀπ᾽ αὐτῶν· ἄνθρωποι δὲ ἐπ᾽ οὐδένας μᾶλλον συνίστανται ἢ ἐπὶ τούτους οὓς ἂν αἴσθωνται ἄρχειν αὑτῶν ἐπιχειροῦντας.

¶ 3

Leave a comment on paragraph 3 58

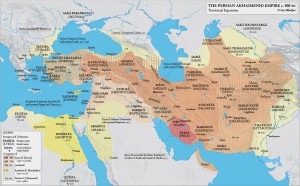

3. Cyrus is the one great exception because he united diverse nations over vast distances…

ὅτε μὲν δὴ ταῦτα ἐνεθυμούμεθα, οὕτως ἐγιγνώσκομεν περὶ αὐτῶν, ὡς ἀνθρώπῳ πεφυκότι πάντων τῶν ἄλλων ῥᾷον εἴη ζῴων ἢ ἀνθρώπων ἄρχειν.  Are human beings born to follow?ἐπειδὴ δὲ ἐνενοήσαμεν ὅτι Κῦρος ἐγένετο Πέρσης, ὃς παμπόλλους μὲν ἀνθρώπους ἐκτήσατο πειθομένους αὑτῷ, παμπόλλας δὲ πόλεις, πάμπολλα δὲ ἔθνη, ἐκ τούτου δὴ ἠναγκαζόμεθα μετανοεῖν μὴ οὔτε τῶν ἀδυνάτων οὔτε τῶν χαλεπῶν ἔργων ᾖ τὸ ἀνθρώπων ἄρχειν, ἤν τις ἐπισταμένως τοῦτο πράττῃ. Κύρῳ γοῦν ἴσμεν ἐθελήσαντας πείθεσθαι τοὺς μὲν ἀπέχοντας παμπόλλων ἡμερῶν ὁδόν, τοὺς δὲ καὶ μηνῶν, τοὺς δὲ οὐδ᾽ ἑωρακότας πώποτ᾽ αὐτόν, τοὺς δὲ καὶ εὖ εἰδότας ὅτι οὐδ᾽ ἂν ἴδοιεν, καὶ ὅμως ἤθελον αὐτῷ ὑπακούειν.

Are human beings born to follow?ἐπειδὴ δὲ ἐνενοήσαμεν ὅτι Κῦρος ἐγένετο Πέρσης, ὃς παμπόλλους μὲν ἀνθρώπους ἐκτήσατο πειθομένους αὑτῷ, παμπόλλας δὲ πόλεις, πάμπολλα δὲ ἔθνη, ἐκ τούτου δὴ ἠναγκαζόμεθα μετανοεῖν μὴ οὔτε τῶν ἀδυνάτων οὔτε τῶν χαλεπῶν ἔργων ᾖ τὸ ἀνθρώπων ἄρχειν, ἤν τις ἐπισταμένως τοῦτο πράττῃ. Κύρῳ γοῦν ἴσμεν ἐθελήσαντας πείθεσθαι τοὺς μὲν ἀπέχοντας παμπόλλων ἡμερῶν ὁδόν, τοὺς δὲ καὶ μηνῶν, τοὺς δὲ οὐδ᾽ ἑωρακότας πώποτ᾽ αὐτόν, τοὺς δὲ καὶ εὖ εἰδότας ὅτι οὐδ᾽ ἂν ἴδοιεν, καὶ ὅμως ἤθελον αὐτῷ ὑπακούειν.

¶ 4

Leave a comment on paragraph 4 17

4. Cyrus was far different from other kings who found it difficult to consolidate their own people…

καὶ γάρ τοι τοσοῦτον διήνεγκε τῶν ἄλλων βασιλέων, καὶ τῶν πατρίους ἀρχὰς παρειληφότων καὶ τῶν δι᾽ ἑαυτῶν κτησαμένων, ὥσθ᾽ ὁ μὲν Σκύθης καίπερ παμπόλλων ὄντων Σκυθῶν ἄλλου μὲν οὐδενὸς δύναιτ᾽ ἂν ἔθνους ἐπάρξαι, ἀγαπῴη δ᾽ ἂν εἰ τοῦ ἑαυτοῦ ἔθνους ἄρχων διαγένοιτο,  How well does Xenophon’s account match the historical record?καὶ ὁ Θρᾷξ Θρᾳκῶν καὶ ὁ Ἰλλυριὸς Ἰλλυριῶν, καὶ τἆλλα δὲ ὡσαύτως ἔθνη ἀκούομεν τὰ γοῦν ἐν τῇ Εὐρώπῃ ἔτι καὶ νῦν αὐτόνομα εἶναι λέγεται καὶ λελύσθαι ἀπ᾽ ἀλλήλων· Κῦρος δὲ παραλαβὼν ὡσαύτως οὕτω καὶ τὰ ἐν τῇ Ἀσίᾳ ἔθνη αὐτόνομα ὄντα ὁρμηθεὶς σὺν ὀλίγῃ Περσῶν στρατιᾷ ἑκόντων μὲν ἡγήσατο Μήδων, ἑκόντων δὲ Ὑρκανίων, κατεστρέψατο δὲ Σύρους, Ἀσσυρίους, Ἀραβίους, Καππαδόκας, Φρύγας ἀμφοτέρους, Λυδούς, Κᾶρας, Φοίνικας, Βαβυλωνίους, ἦρξε δὲ Βακτρίων καὶ Ἰνδῶν καὶ Κιλίκων, ὡσαύτως δὲ Σακῶν καὶ Παφλαγόνων καὶ Μαγαδιδῶν, καὶ ἄλλων δὲ παμπόλλων ἐθνῶν, ὧν οὐδ᾽ ἂν τὰ ὀνόματα ἔχοι τις εἰπεῖν, ἐπῆρξε δὲ καὶ Ἑλλήνων τῶν ἐν τῇ Ἀσίᾳ, καταβὰς δ᾽ ἐπὶ θάλατταν καὶ Κυπρίων καὶ Αἰγυπτίων.

How well does Xenophon’s account match the historical record?καὶ ὁ Θρᾷξ Θρᾳκῶν καὶ ὁ Ἰλλυριὸς Ἰλλυριῶν, καὶ τἆλλα δὲ ὡσαύτως ἔθνη ἀκούομεν τὰ γοῦν ἐν τῇ Εὐρώπῃ ἔτι καὶ νῦν αὐτόνομα εἶναι λέγεται καὶ λελύσθαι ἀπ᾽ ἀλλήλων· Κῦρος δὲ παραλαβὼν ὡσαύτως οὕτω καὶ τὰ ἐν τῇ Ἀσίᾳ ἔθνη αὐτόνομα ὄντα ὁρμηθεὶς σὺν ὀλίγῃ Περσῶν στρατιᾷ ἑκόντων μὲν ἡγήσατο Μήδων, ἑκόντων δὲ Ὑρκανίων, κατεστρέψατο δὲ Σύρους, Ἀσσυρίους, Ἀραβίους, Καππαδόκας, Φρύγας ἀμφοτέρους, Λυδούς, Κᾶρας, Φοίνικας, Βαβυλωνίους, ἦρξε δὲ Βακτρίων καὶ Ἰνδῶν καὶ Κιλίκων, ὡσαύτως δὲ Σακῶν καὶ Παφλαγόνων καὶ Μαγαδιδῶν, καὶ ἄλλων δὲ παμπόλλων ἐθνῶν, ὧν οὐδ᾽ ἂν τὰ ὀνόματα ἔχοι τις εἰπεῖν, ἐπῆρξε δὲ καὶ Ἑλλήνων τῶν ἐν τῇ Ἀσίᾳ, καταβὰς δ᾽ ἐπὶ θάλατταν καὶ Κυπρίων καὶ Αἰγυπτίων.

¶ 5

Leave a comment on paragraph 5 11

5. Cyrus ruled by inspiring both fear and a desire to please him…

καὶ τοίνυν τούτων τῶν ἐθνῶν ἦρξεν οὔτε αὐτῷ ὁμογλώττων ὄντων οὔτε ἀλλήλοις, καὶ ὅμως ἐδυνάσθη ἐφικέσθαι μὲν ἐπὶ τοσαύτην γῆν τῷ ἀφ᾽ ἑαυτοῦ φόβῳ,  How well does Xenophon’s account match the material remains of Cyrus’ reign?ὥστε καταπλῆξαι πάντας καὶ μηδένα ἐπιχειρεῖν αὐτῷ, ἐδυνάσθη δὲ ἐπιθυμίαν ἐμβαλεῖν τοσαύτην τοῦ πάντας αὐτῷ χαρίζεσθαι ὥστε ἀεὶ τῇ αὐτοῦ γνώμῃ ἀξιοῦν κυβερνᾶσθαι, ἀνηρτήσατο δὲ τοσαῦτα φῦλα ὅσα καὶ διελθεῖν ἔργον ἐστίν, ὅποι ἂν ἄρξηταί τις πορεύεσθαι ἀπὸ τῶν βασιλείων, ἤν τε πρὸς ἕω ἤν τε πρὸς ἑσπέραν ἤν τε πρὸς ἄρκτον ἤν τε πρὸς μεσημβρίαν.

How well does Xenophon’s account match the material remains of Cyrus’ reign?ὥστε καταπλῆξαι πάντας καὶ μηδένα ἐπιχειρεῖν αὐτῷ, ἐδυνάσθη δὲ ἐπιθυμίαν ἐμβαλεῖν τοσαύτην τοῦ πάντας αὐτῷ χαρίζεσθαι ὥστε ἀεὶ τῇ αὐτοῦ γνώμῃ ἀξιοῦν κυβερνᾶσθαι, ἀνηρτήσατο δὲ τοσαῦτα φῦλα ὅσα καὶ διελθεῖν ἔργον ἐστίν, ὅποι ἂν ἄρξηταί τις πορεύεσθαι ἀπὸ τῶν βασιλείων, ἤν τε πρὸς ἕω ἤν τε πρὸς ἑσπέραν ἤν τε πρὸς ἄρκτον ἤν τε πρὸς μεσημβρίαν.

¶ 6

Leave a comment on paragraph 6 17

6. What I know about Cyrus’ birth, nature, and education…

ἡμεῖς μὲν δὴ ὡς ἄξιον ὄντα θαυμάζεσθαι τοῦτον τὸν ἄνδρα ἐσκεψάμεθα τίς ποτ᾽ ὢν  From where does one acquire the traits of leadership: (1) family lineage, (2) nature, (3) education? What is Xenophon’s answer to this question in regard to Cyrus?γενεὰν καὶ ποίαν τινὰ φύσιν ἔχων καὶ ποίᾳ τινὶ παιδευθεὶς παιδείᾳ τοσοῦτον διήνεγκεν εἰς τὸ ἄρχειν ἀνθρώπων. ὅσα οὖν καὶ ἐπυθόμεθα καὶ ᾐσθῆσθαι δοκοῦμεν περὶ αὐτοῦ, ταῦτα πειρασόμεθα διηγήσασθαι.

From where does one acquire the traits of leadership: (1) family lineage, (2) nature, (3) education? What is Xenophon’s answer to this question in regard to Cyrus?γενεὰν καὶ ποίαν τινὰ φύσιν ἔχων καὶ ποίᾳ τινὶ παιδευθεὶς παιδείᾳ τοσοῦτον διήνεγκεν εἰς τὸ ἄρχειν ἀνθρώπων. ὅσα οὖν καὶ ἐπυθόμεθα καὶ ᾐσθῆσθαι δοκοῦμεν περὶ αὐτοῦ, ταῦτα πειρασόμεθα διηγήσασθαι.

With respect to the question “who was Xenophon the Athenian?”: another way of asking this is to ask whom his successors believed him to be. What, in other words, was Xenophon’s cultural legacy and where did the Cyropaedia fit into that?

One significant point is that later authors of fictionalized history (or even plain fiction) seem to have adopted “Xenophon” as a coded pen name, e.g. Xenophon of Ephesus, Xenophon of Antioch, and Xenophon of Cyprus; seePerry 1967:167 ff .

I’d also be interested in finding out more about later homages to the Cyropaedia, especially ones which play with notions of genre and authorship. The one I know about is Laurence Sterne’s 18th century novel,Sterne Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy Vol V, Ch 16 . Very roughly, Tristram’s father endeavours to produce a ‘Tristra-paedia’ after the manner of Xenophon to ensure the proper education of his young heir Tristram. But the enterprise doesn’t prosper, as the boy grows up faster than his father can write the work to educate him. The intriguing link is that both the Cyropaedia and Tristram Shandy contain lots of engagement with philosophy and ideas embedded within narratives that are far from straightforward, and challenge notions of genre prevalent then and now.

SeeTatum 1989:3-4 on Tristram Shandy .

I never did get around to finishing it, but what aboutThe Education of Henry Adams ? That is the autobiography of a Boston Brahmin who spent the 1860s in Europe and came back to find a new, commercial, industrial world in the US that his classical education hadn’t prepared him for. I assume the title is an allusion to Cyropaedia, and it has the same ambiguity about whether education is an event in youth or a life-long process.

Thanks for this recommendation! I just ordered it in paperback, though it looks like you can get it for the Kindle for $0.95.

Totally aside, I taughtThe Education of Henry Adams to students at Ablay Khan University in Kazakhstan while I was doing a Fulbright there – I never really saw it in terms of the Cyropaedia. for the simple reason that Cyrus grows in his acceptance of responsibilities, while Henry Adams seems to delight in a sort of seventies-cliche ironic detachment – his education is almost to no purpose, save his own private one – for the record, my students wondered, if all Americans thought and acted as Henry Adams did, how Americans ever accomplished anything.

I am only one chapter into theEducation of Henry Adams (many thanks for the recommendation, Sean!), but already I have noticed several interesting (I do not say intentional) parallels. (1) Adams notes a tension early in life (younger than age 10) between the city of Boston and the country of Quincy. While not exactly modeled on Persia and Media, they are presented in many antithetical ways, the former rigid and lawful, the latter free and sensuous. (2) Adams has a somewhat contentious relationship with his mother (about going to school) and periodically goes to visit his beloved grandfather, John Quincy Adams, in the summer (see p. 10 in the Chalfant 2007 edition). We could relate this to Cyrus’ own contentious relationship with Mandane, insofar as she, too, is concerned about the kind of education Cyrus will receive in Media, particularly in justice. John Quincy Adams, as a former president, might, too, be equated to Cyrus’ Medan grandfather, Astyages, who is also the greatest ruler in all the land. (3) Adams shows a compulsive need to hang around his grandfather’s house and go wherever he wants to, somewhat like Cyrus trying to gain access to Astyages; he, too, wonders if his grandfather favors him, especially above his brothers and sisters (p. 11). (4) Finally, Adams grieves at the death of his grandfather, much like Cyrus worries that his own grandfather might die at Cyropaedia 1.4.2 (cf. p. 16). I wonder if these similarities are just coincidental, if Adams himself noticed them, or if he in fact ever saw himself as another Cyrus and tended to process and relate his own life in those terms.

I was just reading a bit on Alexander the Great today, and I came across an interesting factoid. Onesicritus, a Cynic philosopher and Alexander’s chief helmsman, “consciously imitated Xenophon’s Cyropaedia and tried to turn his Alexander into a philosopher in arms” (Cartledge 2004:276 ). Onesicritus is one of just six eyewitness sources extant on Alexander. I think it would be valuable to compare his work to the Cyropaedia as well as to see how the Cyropaedian tradition of Onesicritus’ work has shaped subsequent narratives on Alexander. In antiquity, Onesicritus’ work apparently prompted Nearchus, one of Alexander’s admirals, to write an account amending Onesicritus’ tale.

BothStark 1958:203-210 and Stadter 1980:60-88 cite several interesting parallels between the narratives of Alexander’s career by Plutarch and Arrian of Nicomedia and the Cyropaedia (#reception #Alexander).

For more on the question of whether Onesicritus is referring to Cyrus the Younger or Cyrus the Great, cf. LionelPearson 1960:89-92 , The Lost Histories of Alexander the Great, and Brown 1962:200 ‘s review (TAPA 83.2). #reception

My question is more related to the development of Greek civilization. I’d like to know more about the evolution of army and governance– which comes first, can you have one without the other, (because enforcement of law is dependent and is depended on by creation of laws)? Does Xenophon consider a successful monarch one who has a good military background? Do the people overthrow governments by violence, and does this relate to the idea of citizen-soldiers? I guess I’m asking about the social context and history in which Xenophon’s ideas of governance developed.

The leading expert on the Greek way of war is ancient historian VictorHansen . Read anything by him, especially his recent books, and you can see how a neo-conservatist uses Greek history to assess US foreign policy, especially when it comes to Israel.

Similarly, the early history of democracy is a very controversial field. India, some of the Punic cities, Greece, and Rome are the best documented cases. I can recommend, but have not read, an anathology edited by StevenMuhlberger of Nippising University as a starting point. I can’t speak to the political history of late 5th or early 4th century Greece in particular very well.

These are all very interesting questions! Let me take a stab at one: Does Xenophon consider a successful monarch one who has a good military background? The short answer is a resounding “yes”, although there are plenty of ways to think about this question. On the one hand, military excellence, exhibited either in the role of a commander or (even better) a warrior, is often the basis even for the privilege to speak in a Homeric assembly. Traits of the good general can readily be transformed into good leadership elsewhere, esp. the military commander’s attentiveness (epimeleia; seeSandridge 2012:51-57 ) and attention to order (eutaxis; see Sandridge 2012:75-76 ). Check out Xenophon Economicus for a lively analogy between the king, the general, and the estate manager/farmer. Generally speaking, in as much as monarchs are expected to provide for the safety (soteria) of their communities, the ability to command an army is a must.

But I would add two qualifications to this rule. It is not always expected that the would-be monarch will risk himself in battle (seeSandridge 2012:107-110 ), and we might detect Cyrus taking more of a back-seat on campaign than other more “heroic” warriors (e.g., Abradatas). Secondly, as armies grow more expert/mercenary in the Greek world (esp. by the Hellenistic period) and as the empire/provenance of leadership expands to many people and many cultures (cf. Cyrus in Babylon by the end of the Cyropaedia), monarchs still cling to the image of a military commander, but this is more a pose than a reality (see Hunter 2003 ‘s commentary to Theocritus Encomium to Ptolemy Philadelphus ).

Finally, while military command is often the basis for a monarch’s legitimacy to rule and while military command can be seen as honing the traits necessary for other kinds of leadership, we should remember that monarchs, as many Greeks conceived of them, needed to be much more versatile than your run-of-the-mill military leader. They needed to be, e.g., (literally or metaphorically speaking) physicians, gardeners, teachers, parents, providers, architects, and even philosophers. Hope this helps! You might also like Godfrey Hutchinson 2000 Xenophon and the Art of Command, esp. his chapter on the Ideal Commander.

Is there a reason Xenophon has this bias against democracy versus monarchy and oligarchy?

I’d be interested to know where you see a bias against democracy?

Would you consider making a “translation diary” a part of the website? I think it could have interesting implications for understanding how a particular student thinks (and struggles) through a translation. It could be made semi-private, or shared with certain people, and might offer an insight into what particular stumbling blocks are most common or what points on grammar should be addressed in the comments (if a student doesn’t know what a construction is, he/she might have trouble articulating, or even considering it, a question). This feature could also introduce discussion about how close a translator should keep to the original Greek, and how far one can reasonably stray. If we made one translation communal, we could keep polishing it and using it as a basis for further discussion on the specifics of word choice and what impacts such choices can have (both in Greek and in translation) on the overall meaning. Do you have any plans on expanding the site to include a communal translation, or are there practical concerns that aren’t occurring to me?

This is a very good question that we will consider further in light of your points. Right now, there is a Comments section available on each of the Lectiones that we hope those processing/translating the text will use to ask questions and to share their own challenges and solutions (have you tried it? do you find it helpful?).

Your thinking is right in line with ours on the matter of the communal translation. It is definitely something we would like to build into the commentary down the line. We could thus allow anyone to comment on the translation just as we may comment on the Greek text. Such a medium would illustrate well how much is lost in translation and how our own interest in the text can govern what we decide to keep and leave out from the Greek.

Thank you! Yes, I’ve been reading many of the comments on each chapter, and it is very helpful in placing the text in its proper historical/social context. I certainly find it an excellent space for discussion and expanding my worldview, and in that sense it is more than satisfactory, but the translation could add a whole new dimension. Thank you for fielding so many questions! This is an amazing project.

As someone still struggling to become a comfortable reader of Classical Greek, I think that an online commentary like this has great potential to bridge the traditional gap between the authors of a new student edition and their imagined audience. It can’t be easy to guess what points will trip people up, or to remember what problems people seemed to have when you taught this text last spring. It also seems to me that we don’t always talk about general issues and methods in translation as much as we should, so some kind of online discussion about problems could be helpful whether or not it turned into a full translation.

I couldn’t agree more, Sean, and, as with Melissa, I would encourage you to pose the most challenging questions you can think of in the Lectiones section. Every time I think Xenophon’s supposedly simple, elegant Greek has become formulaic, I’m impressed by how carefully he chooses his words and varies his expression, often for more than stylistic reasons.