Xenophon’s Cyropaedia and Persian Oral History: Part Three

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 See also the Blog Page for Parts One and Two

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 Cyrus’ Peaceful Death

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 The vast majority of classical authors concur that Cyrus died in battle against the Central Asian nomads living beyond the northeastern frontier of his empire. The Cyropaedia (8.7.2–28) goes against the grain by ascribing to the conqueror a peaceful death. The common perception is that Xenophon deemed a violent death unbefitting for the hero of his work and manipulated the facts accordingly. Indeed, Cyrus’ moving deathbed speech in the Cyropaedia affords Xenophon the opportunity to impart a few more philosophical lessons on statecraft and filial loyalty. However, deathbed speeches of the sort frequently appear in the Iranian epics, and the late Heleen Sancisi-Weerdenburg and others have identified possible Iranian themes in Cyrus’ final address.[1]

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0 I would like to develop this view further, by exploring the possibility that Xenophon did not himself create the tradition that Cyrus died peacefully but, rather, based his account on an authentic Iranian tale about the Persian conqueror. To do so, I will venture to reconstruct the full form of the Cyrus saga recounted by Herodotus (1.107ff), which, as we will see, is unlikely to have attributed a violent death to the conqueror. I will then show how Xenophon’s account of the conqueror’s demise suggests familiarity with this “lost” version of Cyrus’ death.

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 In relating Cyrus’ story, Herodotus (1.95, 1.214) repeatedly states that he had heard different versions of the conqueror’s biography from the Persians but that he had chosen for his own narrative the accounts that seemed the most believable to him. The other accounts, Herodotus says, glorified Cyrus unduly. This is an important point to keep in mind. The first part of the story Herodotus relates may be summarized as follows: Astyages, the king of the Medes, has a series of nightmares foretelling that his daughter Mandane will have a son who will overthrow his kingdom. To allay the threat, Astyages marries Mandane, not to a Mede, but to the Persian Cambyses, whose mild habits make him unlikely to cause trouble. Later, when the child is born, the Median king contrives to eliminate the threat more decisively by killing the infant. So he orders his steward, Harpagus, to abandon the infant in the wilderness. Wanting no part of the infanticide, Harpagus entrusts the grisly task to the shepherd Mithradates, whose name means “Given by Mithra,” a subtle reminder of the deity deemed responsible for the child’s ultimate salvation. One variation of the legend claims that Mithradates actually abandoned the child in the woods, only to witness a she-dog defend the baby against other wild animals and give it milk. According to another variation, Mithradates had a wife named Spaco, whose name meant “dog” in the Median language and who had recently given birth to a still-born child (Cyrus’ figurative twin in the legend).[2] On her advice, Mithradates dupes Harpagus into thinking that he has carried out his task by presenting him with the body of his own dead child, wrapped in the golden swaddling cloth of Prince Cyrus. Both variations have the shepherd raise Cyrus until he is ultimately restored to his true parents. Afterward, Cyrus vanquishes Astyages with Harpagus’ help.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0 The same basic story appears in the Persian epics, specifically in the Shahnameh’s account of the rise and origins of Kavi Husravah. As indicated above (see Part One), there appears to be a relation between the Cyrus sagas and the tales of this epic hero. A similarly strong resemblance occurs with the Roman legend of Romulus.[3] In this legend, Romulus, the father of the Roman nation, is a descendant of King Numitor of Alba Longa. Numitor is driven from his kingdom by his treacherous brother who then conspires to kill the dethroned monarch’s family. The usurper condemns Romulus and his twin brother Remus to death by abandonment along the River Tiber, but his plan is foiled when a she-wolf saves and suckles the infants. Later, a shepherd and his wife find the infants and foster them to manhood. The shepherd is named Faustulus or Faunus after the protective deity of wild forests.

¶ 7

Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0

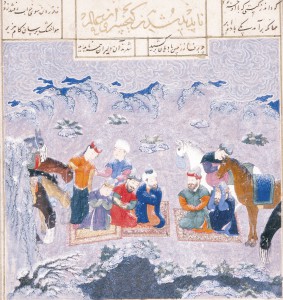

Kay Khosrow (Kavi Husravah) and his Companions Disappear in a Blizzard (From Fathers and Sons: Stories from the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi, translated by Dick Davis, courtesy of Mage Publishers)

Kay Khosrow (Kavi Husravah) and his Companions Disappear in a Blizzard (From Fathers and Sons: Stories from the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi, translated by Dick Davis, courtesy of Mage Publishers)

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 One version of the legend refers to his wife as a prostitute, the Latin term for which is lupa, meaning “she-wolf” (the Romans equated the lowest level of prostitutes with female canines).[4] Her name thus directly recalls that of the shepherd’s wife in the Cyrus saga. The existence of a very old Indo-European literary framework could not be more evident.

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 The similarities between Herodotus’ Cyrus saga, on the one hand, and the legends of Kavi Husravah and Romulus, on the other, are significant, for both Romulus and Kavi Husravah leave this earth peacefully, albeit under special circumstances. In the Roman myth, Romulus, learning that his subjects have grown weary of kingly government, offers public sacrifices at or near a prominent hilltop. Soon thereafter, he disappears in a storm or whirlwind and his soul ascends to heaven, where it assimilates with the spirit of Quirinus, a god of war and social order.[5] Kavi Husravah meets a similar end in the Shahnameh. Wary of the pitfalls of autocratic power, he fears that he might abuse his authority if he were to remain king. He dreams of the angel Sorush, who tells him that the time has come to leave this earth. This angelic visitation distinguishes Kavi Husravah from previous kings, with whom Sorush had not communicated.[6] Husravah then sacrifices to the gods and, after bidding farewell to his friends and family and selecting an heir, ascends a mountaintop where he vanishes in a blizzard. The Shahnameh gives no indication of his assimilation with a deity; but Ferdowsi wrote the Shahnameh during the Islamic period, and some redaction of blatantly pagan elements is to be expected.

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0 The existence of a tale regarding Cyrus’ death structured on the same literary framework as the legends of Romulus and Kavi Husravah seems probable based on Xenophon’s account of the conqueror’s demise. The basic elements of Xenophon’s story are as follows: An angelic being visits Cyrus in a dream and informs him that he must “soon depart to the gods.” Cyrus immediately ventures to a high place and performs acts of worship. He then summons his family and friends to his side, names Cambyses II as his successor, and bids farewell to those gathered, but not before offering a few final admonitions regarding the pitfalls of selfish behavior. As noted by Deborah Gera, this farewell address closely resembles that delivered by Kavi Husravah in the Shahnameh.[7] Xenophon’s account thus contains almost all the same major elements as the tales of Romulus and Kavi Husravah.

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 The only significant disparity concerns the hero’s occultation. But Xenophon was a rationalist, and as indicated above, the Cyropaedia is notoriously lacking in supernatural elements. Also, Cyrus’ entombment at Pasargadae was a well-known fact among the Persians, so the legend must have been adapted to no longer state that the hero’s body had disappeared.[8] On the other hand, a Persian belief that Cyrus’ soul departed this earth to attain a higher level of existence seems likely from the testimonies of the Alexander historians. According to Arrian (6.29.7), the Magi performed monthly horse sacrifices in Cyrus’ honor at the site of his tomb at Pasargadae, in the Persian heartland. Among the Iranians of Cyrus’ day, the horse sacrifice constituted a special rite in the cult of the sun god Mithra, who functioned also as a god of war and social order. Thus, Herodotus (1.216) tells of the Massagetae, an Iranian tribe from Central Asia: “The only god they worship is the sun, and to him they offer the horse in sacrifice; under the notion of giving to the swiftest of the gods the swiftest of all mortal creatures.” According to Strabo (11.13.8, 11.14.9), the satraps of Media, Armenia, and Cappadocia forwarded thousands of sacrificial horses to the Persian kings of the fourth century bce as tribute during the “Festival of Mithra.” In Indo-Iranian lore, the horse sacrifice (Vedic asvamedha) functioned as a generic royal funerary rite, the purpose of which was to bring the deceased chieftain’s soul closer to light.[9] However, such offerings are unattested in connection with other Achaemenid rulers, thus bespeaking the special association between Cyrus and Mithra. Corroborating this association is Plutarch’s assertion (Life of Artaxerxes § 1) that Cyrus obtained his name from the sun. This statement is indefensible on etymological grounds but seems to evince the memory of Cyrus as a Mithra-worshipper. Indeed, Amelie Kuhrt has suspected that Plutarch’s testimony indicates Cyrus’ assimilation with Mithra, which, of course, recalls Romulus’ supposed conflation with the god Quirinus.[10]

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 Conclusion

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0 The study of ancient Iranian history and, in particular, Cyrus’ life and times is, as I have found while writing my book, a complicated undertaking. Due to the oral bent of early Iranian society, the historian must triangulate and closely scrutinize all the sources at his disposal. These include cuneiform records, biblical texts, legends, artistic and architectural remains, linguistic data, and, most importantly for purposes of reconstructing a coherent narrative of events, the Greek sources, of which Xenophon’s Cyropaedia is an important and sometimes overlooked example. A truly interdisciplinary approach is necessary, and while this may seem daunting, much room still exists for new and informative insights and perspectives.

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 [1] See Sancisi-Weerdenburg (1985); Gera (1993), 116–117.

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 [2] Herodotus’ “spaco” reflects Median *spaka, cognate of Old Persian *saka, which leads to New Persian sag.

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 [3] See Dunlop (1888), Table 2, “Aryan Exposure and Return Formula,” translated by Henry Wilson from J.G. von Hahn’s Sagwissenschaftliche Studien, Jena, 1871. The table identifies the legendary accounts of fifteen Indo-European heroes, including historical personages and mythological characters. The similarities between the legends of Cyrus, Kavi Husravah, and Romulus seem most striking.

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 [4] See, e.g., Plutarch Life of Romulus § 4; Livy 1.4.

¶ 19 Leave a comment on paragraph 19 0 [5] See, e.g., Plutarch Life of Numa Pompilius § 2; Life of Romulus § 26–29. On Quirinus as a god of social order, see Versnel (1994), 332, fn. 139.

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 [6] Indeed, Ferdowsi has the Iranian noblemen marvel that “the angel Sorush never appeared to a king before,” although earlier in the Shahnameh Sorush appears before the kings Keyomars and Feraydun. Inconsistencies of this sort abound in the Shahnameh, but it is possible that Ferdowsi derived his story of Kay Khosrow from a different source. See Davis (2007), 365; Khaleghi-Motlagh (2009–2010), 264–265.

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0 [7] See Gera (1993), 116–117.

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 0 [8] Elements of the occultation myth exist even within Herodotus’ account (1.214ff) of Cyrus’ death, which follows a different trajectory and has the conqueror fall in battle against the Central Asian Massagetae. For example, Herodotus’ Cyrus acts more autocratically at the end of his reign. Scholars tend to interpret this detail in terms of Herodotus’ penchant for Attic tragedy and belief in the intrinsic shortcomings of absolutism. However, the contribution of Iranian literary motifs cannot be ruled out. More to the point, Herodotus has Cyrus fall in battle three days after passing beyond the borders of his empire. According to ancient Iranian belief, three days signified the time necessary for a deceased person’s soul to ascend to heaven. Thus, per the story, Cyrus’ soul had effectively already left this world by crossing over into enemy territory. To support this interpretation, one might cite another feature of Herodotus’ account. Like Kavi Husravah, Herodotus’ Cyrus dreams of an angelic being: in this case, the future emperor Darius I, who appears in the vision with wings on his shoulders. According to Herodotus, the dream signified Cyrus’ imminent demise and Darius’ eventual succession. The reference to Darius is significant from the standpoint of literary criticism, because it indicates that Herodotus’ story of Cyrus’ death derived from a different source than the one from which he heard the saga of the Persian founder’s origins, in which neither Darius nor his ancestors play a part.

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 [9] See Daryaee (2013), 23–24.

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 [10] See Kuhrt (2007), 565: “Plutarch’s statement is enigmatic, but could relate to the special place occupied by Cyrus the Great in Persia’s vision of the heroic past, with Cyrus’ heroic persona merged with that of a major deity.”

[…] Xenophon’s Cyropaedia and Persian Oral History: Part Three […]

Comment awaiting moderation